Some places endeavour to be a home. At Appetite, that connection forms before you notice—from the minute you slip in the door, having scaled a narrow flight of stairs and rung the doorbell you found waiting at the top. When a member of staff opens the door and ushers you in warmly, you’ll see that the walls are lined with art (curated exhibitions that are swapped out every three months) and the unmistakable sound of vinyl fills the space. You may think for a second that instead of a restaurant, you’ve entered somebody’s chic apartment dressed for a house party. Tucked away in the heart of the hip dining enclave of Amoy Street, that is unlikely, but the feeling is there all the same.

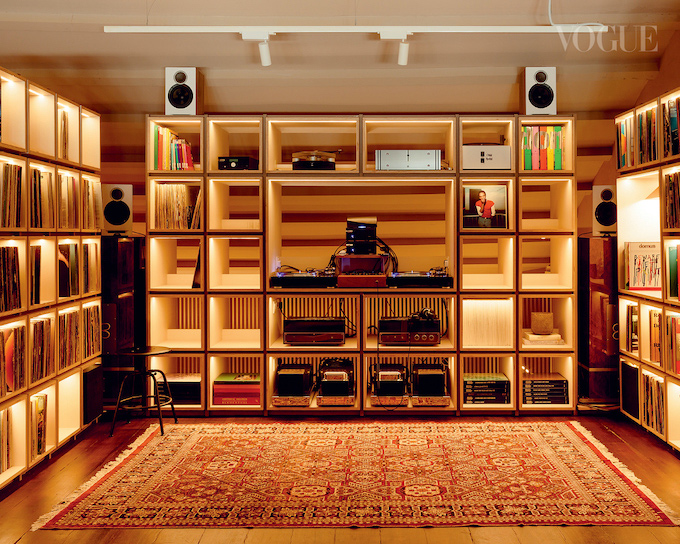

Upon stepping into the two-storey space, you’ll be guided either to the Omakase Room (an open kitchen dining area for sit-down service), or one of the living room sections filled with couches and small side tables. The latter, especially the biggest space known as the Listening Room, immediately subverts expectations of what a fine dining restaurant should look like today. Shrouded in comforting dim light, the room is lined with plush couches soft enough to fall asleep on. But the real star of the space is the music set-up—dozens of speakers, two turntables and a hunkering record collection of old-school vinyl. On any given night, you can expect a themed playlist spotlighting a particular artist, era or genre. Patrons can sit where they wish (as long as COVID-19 regulations are maintained) and nurse a drink, while enjoying what Michelin-starred head chef and founder Ivan Brehm dubs small plates.

Brehm has cut his teeth in the kitchens of Per Se in New York, Hibiscus in London, Mugaritz in Spain’s Basque region and Heston Blumenthal’s The Fat Duck. He then launched Restaurant Nouri in 2017, leading its kitchen to a Michelin star in its first year. But his curiosity about food hardly ends at cooking. What the 36-year-old is truly fascinated by is the study of food as material culture—how what we eat has come to represent who we are as people. This you see exemplified in his menu, each dish carefully considered to bring together a melange of references and experimental techniques establishing oft-overlooked connections in our world.

Brehm’s favourite dish on the bites menu is Tortilla de Camarones— irregular discs of tempura served alongside a creamy portion of shrimp, grapefruit and lime. The origins of tempura, in this case, are of particular interest to Brehm. “This dish intends to tell the story of fried food. If you’ve been to Cambodia, you’ll see street vendors selling tarantula tempura. All of those variants, including Japanese tempura, originated in Europe. Europeans, specifically in Portugal and Spain, learnt how to do that through interactions with the Arabs,” shares Brehm. “Our Tortilla de Camarones is a very abridged and direct way of communicating that unbroken link that blanketed over Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, all the way to Japan.”

The menu also features a particularly luscious bowl of corn custard and uni, bursting with complex flavour and texture. Brehm explains: “To make the custard, we steam corn juice and let it set—almost like tofu. There are a lot of analogous customs to this in Brazil and South America. You would also find things like this in Thailand, in desserts, maybe wrapped in corn husks. We then steam the custard with an uni sauce on top of it, before adding in a few pieces of uni and a stir-fry of corn in lime.”

A few dishes in, it’s hard to miss that the common thread running through the menu is one of cultural crossroads. “What you’ll start to see is that even if the ingredients in two different food traditions are different, the treatment or the flavour profile could be similar. People are seeking the same things. You start to realise some pretty crazy statements about the universality of humans—regardless of their places in time,” says Brehm.

“The goal ultimately isn’t to make people let go of their own traditions. Instead, we want them to interrogate their traditions and realise that they are nested in a larger tradition”

Given the kind of anthropological theory Brehm shares off the cuff, it may come as no surprise that Appetite doubles as a research centre. If you think of the dining space within the traditional confines of what a restaurant is supposed to be, the presence of the research arm doesn’t intuitively follow. But as head of research Kaushik Swaminathan explains, without the genesis of the research centre, restaurant Appetite would have never come to be.

“In order for us to continue cooking creatively and constantly innovate, we realised that we needed to dive deep into certain historical and anthropological trade routes, and ultimately understand the ways in which food cultures have evolved over time,” Swaminathan shares. “We started this from a vocational point of view—our chefs would taste two ingredients from different parts of the world. But as vocational professionals, they were able to recognise patterns in those flavours, which then made us want to investigate whether there were actual connections that were verifiable across time. To look for those connections, we had to work with scholars—historians, anthropologists, sociologists and linguists—largely people in the humanities professions.”

According to Swaminathan, the central question that Appetite’s research arm centres on is: what happens when people move? “What happens when people are forced to travel? How can we find an expression of globalisation and of multiculturalism and food? We’re ultimately thinking and fundamentally about cultural evolution, migration and globalisation,” he explains.

The enthusiasm coming from Swaminathan is palpable. Each member of the Appetite team works multiple roles and pulls incredibly long hours. It’s clear that they believe immensely in what they do and have great pride in the experience they have created. “We tend to attract people who are particular about their work, people who really have something to show and believe that they can constantly do better,” says Brehm.

The kitchen team, other than Brehm, is made up of a majority of women. If you peek into the food prep area in the busy few hours before dinner service, you’ll see them flitting around the countertop like butterflies, each rapidly working on multiple dishes at the same time. In an industry typically dominated by the male gender, Brehm confirms that hiring predominantly women was a deliberate choice. “Obviously, aiming for gender equality is important and that was a concern for us too. But on the practical side of things, I’ve been in hot, sweaty kitchens full of just men. Objectively, the work is worse. It’s aggressive, it’s irresponsible and it lacks teamwork. Having a balance and a mix is very important.”

The experience they wish upon their patrons is one that the team at Appetite experience everyday—an intimate examination and questioning of their own heritage and notions of identity. “People in Singapore are religious about food. They have such a discerning palate here. So we seduce them in with the cooking, even if the art and the music isn’t their primary interest. Then it turns out that the people who are saying, within their first 15 minutes of arrival, ‘What is this weird thing on the wall?’ are the same people who, after three hours, are looking more intentionally and more closely at a work of art than they ever have in their lives before,” laughs Swaminathan. “By being in this space, by thinking about the role that art and music and food plays in your life, it actually affects you emotionally and personally. It feels magical and it feels new.”

Brehm sums it up: “The goal ultimately isn’t to make people let go of their own traditions. Instead, we want them to interrogate their traditions and realise that they are nested in a larger tradition. And that we may be a product of our experiences over time, but at our hearts, in essence, we’re all very much part of a larger family. If we can understand that, then not only can we validate our own traditions, we’ll stop feeling like we need to protect ourselves from our neighbours. Because we’ll realise that these borders we’ve internalised—they’re all arbitrary.”

Deputy Editor: Amelia Chia

Photography: Sayher Heffernan

Grooming: Greg’O

For more stories like this, subscribe to the print edition of Vogue Singapore.