Cyber-style received an unprecedented push into mainstream culture as a result of the pandemic. For much of 2020, many fashion brands shelved their in-person catwalk shows, choosing to opt instead for virtual reality shows or short films to showcase their collections. There was the Gucci-Pokémon partnership, which saw the fashion house designing for player avatars. The Aura Blockchain Consortium, created in collaboration with LVMH, Richemont and the Prada Group. The Balenciaga AW21 video game.

In the fashion world’s heated atmosphere of digital innovation, ambitious ventures have sprouted up, looking to capitalise on the demand for virtual threads. One such company is Singapore-based Republiqe, run by James Gaubert, which was launched in August of 2020. The world’s first digital-only luxury fashion brand, Republiqe is founded on a bedrock of Gaubert’s experience in “analog” fashion. He’s a designer and stylist who has worked with everyone from Chanel and Burberry to Bulgari and Louis Vuitton. With 22 years in the industry, he’s seen it all—but he never could have predicted his next gamble being something like Republiqe.

“I think I always dreamt of having my own fashion label—but very much in a physical sense,” he says during a recent Zoom interview. Patching in from his home office, his dog snoozing behind him, he adds, “If you told me ten years ago that I’d be running a company where we manufacture clothing that doesn’t physically exist, I would have thought you were absolutely bonkers. But we have no idea where [fashion] is going next. That, to me, is part of the appeal.”

Republiqe, Gaubert explains, is all about creating an “inclusive, ethical, sustainable, and creative alternative” to physical clothing. “Let’s be honest, the fashion industry is not renowned for its sustainable, environmentally-friendly approach to manufacturing,” he says. Every cyber-garment can be manufactured (or rendered, if you like) with a fraction of a fraction of the energy it would take to create it physically.

Republiqe’s first collection comprised 22 digital garments, and the company has expanded stratospherically since then, dropping new collections to coincide with special occasions and holidays. Every article of clothing can theoretically be made an infinite number of times, so stock never runs low.

“We’re not here to displace physical clothing. We all still need to actually wear clothes. But what we do is in addition to that,” Gaubert explains. “Rather than spending money on a garment you only wear once, for social media, why not spend less money on a digital version of it? And have less impact on the environment.”

One size fits all, as the brand’s tailors will digitally dress the customer in their purchased cyber-garment. Otherwise, purchasing from Republiqe is mostly like any other online shopping spree: browse through the catalogue, add to cart, purchase. After that, however, you’ll upload a photo of yourself, which gets sent to the 3D-tailoring team, who fit the garment and send it back.

This final product—essentially, a .jpeg—means that most of Republiqe’s customers are young millennials and Gen Z’ers. Gaubert, who by his own good-humoured admission is the oldest person working at Republiqe, knows that there’s a market for what he does. He’s watched his son spend enough money on purchasing skins for his Fortnite avatar, after all. “There’s similar elements there, helping people to build their social personas and presence through creative clothing.”

He might have something there. The demand for Fortnite skins is valued somewhere in the neighbourhood of $40 billion a year. Fashion brand Auroburos has found great success selling garment collections on fashion game and marketplace Drest. It might be incomprehensible to older folks, but the younger generations value their digital selves just as highly as their physical ones. And that calls for digs that look good on Instagram or TikTok.

Cool clothes, in the physical world, are often prohibitively expensive. By virtue of how it does what it does, with no factories or materials and just a small, dedicated team of designers, Republiqe is comparatively affordable. Its set-up also allows it to do the impossible, literally. Clothes made of concrete? You got it. Broken shards of reflecting mirrors? Life-threatening in the real world; totally doable in the virtual space. Real PVC trousers would be impossibly hot and heavy, but online they’re lighter than air.

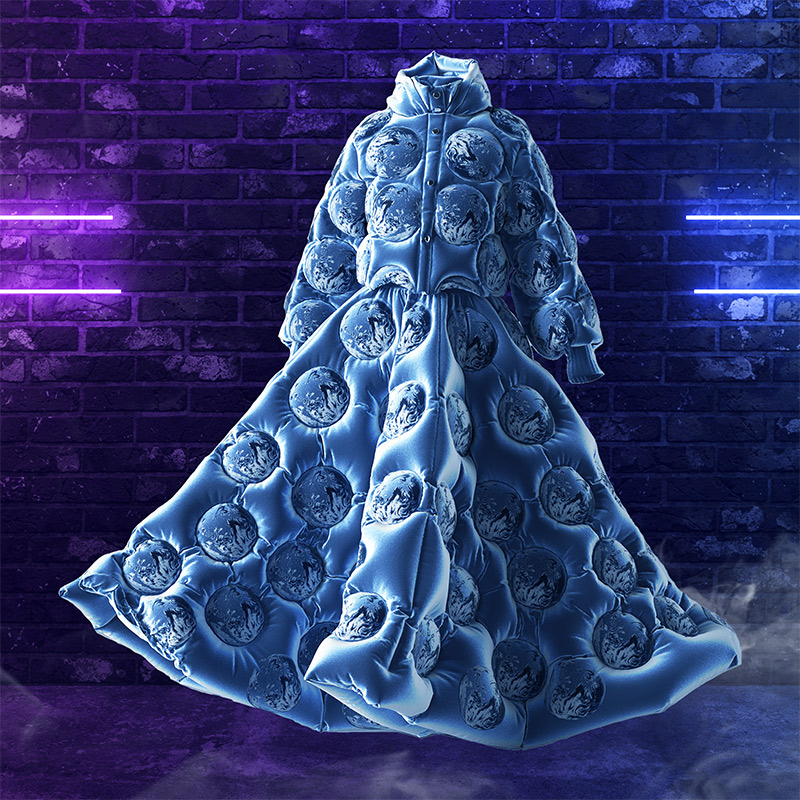

Those whose jaws drop and monocles pop reading about this kind of fashion need not proceed any further. This is because Republiqe has taken a step deeper into the digital universe, minting and auctioning off its first set of NFTs in April and May. The limited-edition bespoke set of a matching puffer jacket and a dress was launched in celebration of World Health Day. The winning bidders had their photos e-tailored, and were also sent the “raw files” used to create the garment. Those files are encrypted with the all-important serial number that tracks ownership indefinitely.

For better or for worse, NFTs are rapidly colonising a good chunk of the artistic world. An asset class touted by cryptocurrency fiends, a non-fungible token essentially describes a way of storing data—a record of ownership—on the digital ledger known as the blockchain. Ostensibly, an NFT you purchase is one of a kind, though critics would argue it’s like dropping millions to buy the receipt to a GIF. It’s an undeniable phenomenon, though, most commonly illustrated by the $69 million auction of a Beeple NFT artwork.

A frequent criticism of NFTs is their environmental impact; “mining” the transactions contributes to a usage of energy comparable to that of a small country. This kind of consumption might, it could be argued, negate Republiqe’s sustainability ethos. Gaubert’s answer to that is to remind critics to keep things in perspective. “There is a carbon footprint associated with creating NFTs. I can’t deny that or hide that,” he says. “However… it’s still better than creating physical clothing. Our carbon footprint, in comparison to traditional clothing manufacturers, is next to nothing.”

Wherever NFTs are headed, Republiqe wants to be along for the ride. “There are absolutely no signs of it slowing down,” Gaubert explains. “So while we’ll continue to run our e-commerce shop and sell digital clothes directly to consumers, this is just a different route to market. And I feel like it’s helping us reach a completely different audience.”

When Gaubert sat his mother down last year to explain what he was doing at Republiqe, her eyes glazed over. She wasn’t his target demographic, though, so he wasn’t too worried. And already, more and more people are getting it. Part of that is thanks to the bigger kids on the block lumbering into the space—Gucci’s virtual trainers, for example, were apparently just the beginning, as a source told Vogue Business that “it’s only a matter of time” before the brand’s first NFT is created. Other houses are following suit, but again, Gaubert isn’t concerned. Instead, he’s excited. “I’m encouraged when I see other brands doing digital clothing. I don’t sit there thinking, Oh no! I’ve got competition,” he says, grinning. “I see that as validation of what we’re doing.”

Where to next? Competing for the Vogue Singapore x TaFF Innovation Prize, for one thing. One of ten finalist businesses selected for a two-day bootcamp and four-week mentoring session, Republiqe will craft a business plan with baked-in sustainability, scalability, and strategy. Should they win, there will be a monetary prize, seed funding, and connections to a global network of industry titans. Either way, though, Gaubert is clear-eyed about the future. “In the two decades I’ve been working in fashion, it’s been the same as it’s always been. The faces change, the styles change,” he says, “but apart from that there’s never been a real seismic shift with regard to the process of manufacturing and creating clothing. Until now. Now, I think we’re really on the cusp of something different.”