After New York and Tokyo, Francesco Risso brought his spring collection for Marni to Paris “to continue amplifying connections among our global community,” he said at a preview. “I’m in a flâneur state of mind.” It sounded like he was giving the word “peripatetic” an ineffable coating of je ne sais quoi. Showing in the Ville Lumière also gave him permission to savour bites of some rather personal Proustian madeleines.

The day before the show, previews were held at the OTB headquarters, in whose attic Risso and his crew had been “squatting” to prep for the show, transforming the space into a Marni-fied kids’ playground—walls and floors hand-painted with skies, shooting stars, and comets, with vivid fleurs en découpage scattered everywhere. Risso recounted that the idea of showing in Paris came “from a scent and a crossover of coincidences.” The first time he visited the city he was 14, and at a party he met by chance “a beautiful creature, who suddenly disappeared, leaving behind only a faint whiff of perfume,” he explained. That subtle French flutter haunted him for years, making him travel to Paris only in the hope of smelling it somewhere again. He never found it, but the magic of Paris was forever imprinted in his memory and olfactory functions. That was the first madeleine.

The second was less elusive and more fortuitous. As a teenager, Risso used to visit his friend Serena in Paris at her parents’ house in the chic 7th arrondissement; their neighbour was the late Karl Lagerfeld, whom they spied on obsessively, waiting for him to appear all-black clad in Rue de l’Université “as if he were Michael Jackson.” Recently, scouting for this show’s location, Risso was presented with the possibility of using Lagerfeld’s little Versailles. Et voilà—dots were connected.

The private apartments and the formal gardens of the fabulous hôtel particulier where Lagerfeld spent many years were colonised by Marni and its audience, who sat (rather wobbly) on tubular white inflatables (a Risso fixation) snaking through the opulent gilded salons. A series of small orchestras, dressed in surgical white vinyl lab coats, performed music by Dev Hynes, a frequent Risso collaborator. Almost 45 minutes past showtime, Usher and Erykah Badu made their majestic entrance—him wearing a red-flame polka-dotted puffy ensemble, her sporting a trailing cape and a hat so monumental, you only felt grateful not to be seated behind her.

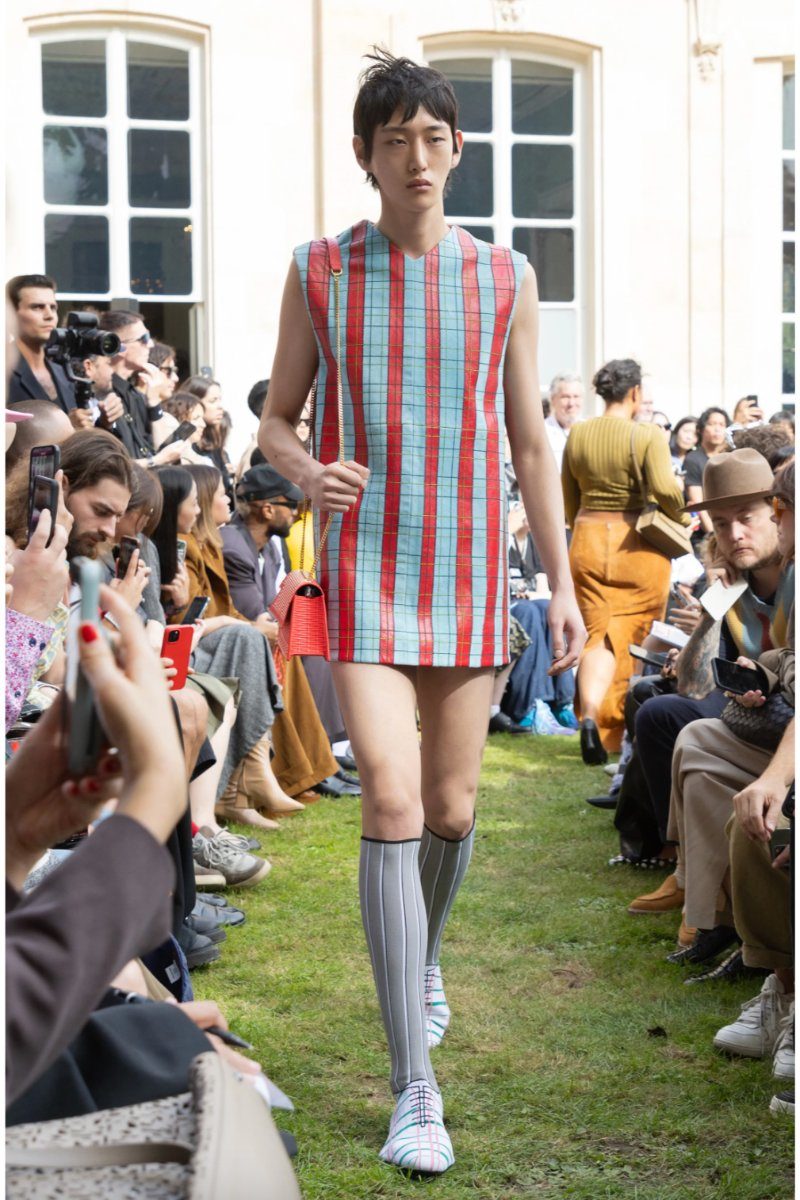

The co-ed collection’s flow had a sort of interrupted progression. It started with lean, light, tight-fitting ribbed tube tops in various lengths, to underline the body celebration that’s inherent to Risso’s discourse (“it’s the body in its natural state, not as an ostentatious tool of self-communication,” he said). Then the show segued into a series of sartorial specimens variously combined: oversize trapeze or boxy-cut tops worn under sharp-tailored trench coats and dusters, paired with straight-cut pants or undulating miniskirts. Most of the pieces were made in soft-bonded techno knitwear to keep their angular shape, rendered into the rainbow-coloured combinations of textural checks and stripes that’s a Marni trademark. They had a wearable, realistic quality about them, energised by Marni’s pyrotechnic palette.

A few undone crinolines in saturated pastels (uncertain Ladurée shades of raspberry and apricot merengues) with apron tops left open at the back and voluminous bell-shaped ankle skirts brushed past the front row, hinting at the obvious reference to the frivolous queen of “let them eat brioches” fame. “I wanted to give a physicality to those pieces,” said Risso. “Not because they had to look surreal, rather because I wanted them to occupy a space, and to be touched and experienced in close proximity by the audience.”

The crinolines then sort of exploded into the show’s pièces de résistance: a series of exceptional concoctions of fleurs en découpage—visually enchanting, painstakingly handmade creations that Risso called “the ecstasy of the hand.” Hundreds of bright-coloured images of flowers, sourced from antique botanical almanacs, were printed on cotton, individually cut out, and then patiently stitched onto bustier dresses with round-shaped crinolines, poufy miniskirts, and a skirt suit with round, jutting shoulders. They had magic. Adding further wonderment, discarded tin cans were moulded into flowers that stemmed, protruded, or sprouted from body-skimming minidresses. Rather ominous looking, they were spectacular runway pieces not intended for a long shelf life—yet they raised the show’s visual vibes to a transporting place, where fashion is absolute joy of creation as well as rebellion in the face of the mundane laws of reality. “This is the virtuosity of the hand that goes against pervasive virtuality,” said Risso. “We’ve got to undress our mind, and dress up our senses.”

1 / 12

2 / 12

3 / 12

4 / 12

5 / 12

6 / 12

7 / 12

8 / 12

9 / 12

10 / 12

11 / 12