Previous collections have seen JW Anderson look off-runway and instead to unconventional methods to present his seasonal showcases. The designer called upon Juergen Teller to capture his artistic autumn/winter 2021 presentation; delivered via a tube of images printed on thick paper stock.

Having forged relationships with Dame Magdalene Odundo and Shawanda Corbett during the lockdown period, he invited the artists to contribute work that was subsequently emblazoned across blankets that enveloped some of the 19 looks seen in the collection.

Here, British Vogue’s fashion news director Olivia Singer speaks with the designer about his latest release.

1 / 5

It was the latest in Anderson’s series of immersive interventions

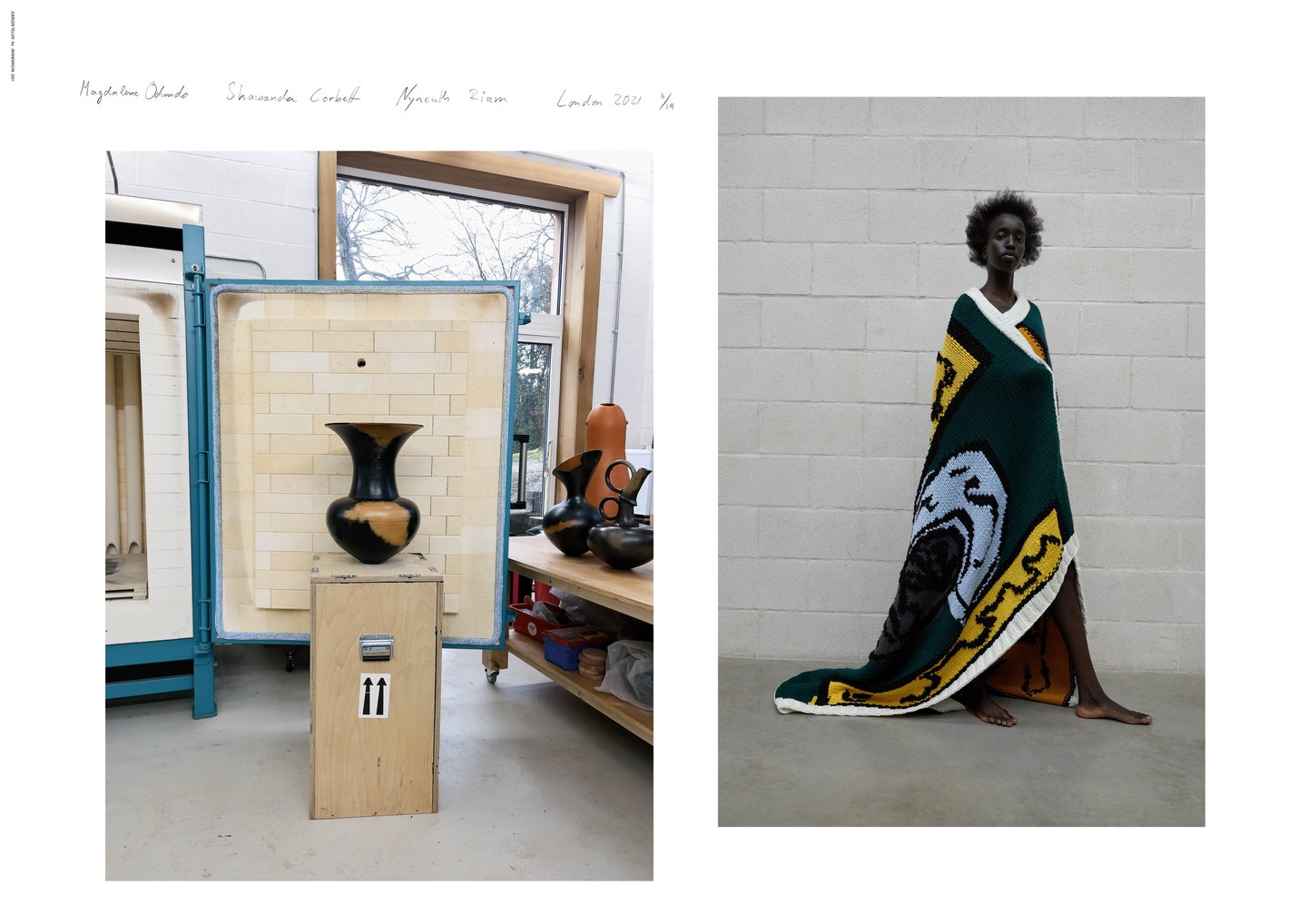

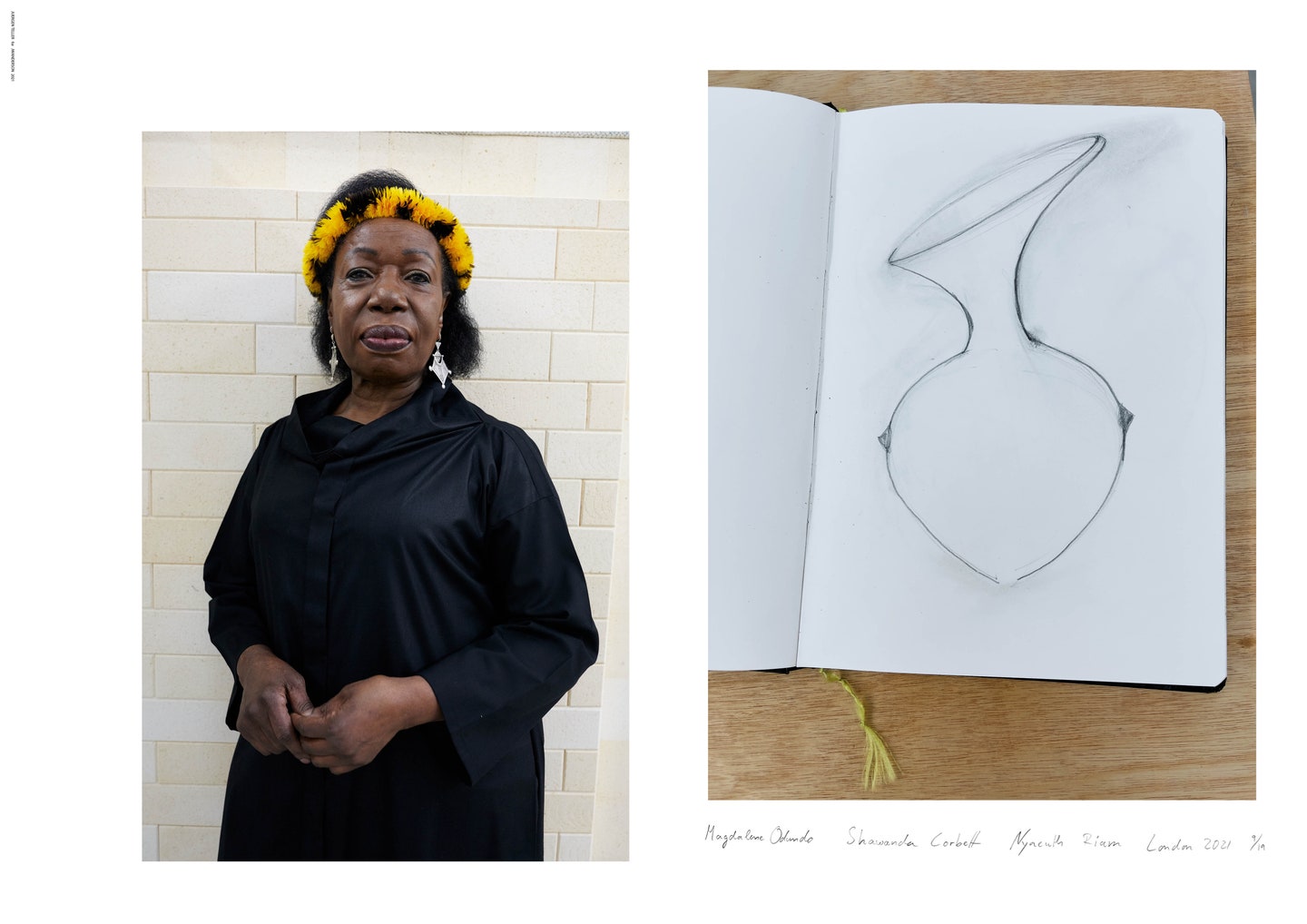

Over the course of the pandemic, Jonathan Anderson has sought various ways to remotely present his collections—both for his eponymous brand and Loewe—without succumbing to a live-streamed runway. By this stage, most editors have living rooms filled with assorted Anderson-related paraphernalia; we’ve had shows in boxes and printed on T-shirts, rolls of wallpaper and reams of posters. This time was his second iteration of the latter: a tube of Juergen Teller images, printed on thick paper stock, was the medium through which he presented his autumn/winter 2021 collection—and, while it might sound the simplest, it was perhaps the most intricately conceived yet. Photographs of JW Anderson looks were interspersed with still lifes and sketches of ceramics by Dame Magdalene Odundo and Shawanda Corbett, portraits of the artists, and imagery of the limited-edition blankets each of them designed to accompany the collection. It read more like an exhibition catalogue, or a mind-map of Anderson’s, than the distillation of a runway.

Its assembly reminded the designer, he said, of his remarkable 2017 Hepworth Gallery exhibition Disobedient Bodies—an experience which “became almost like a quest, or a dissertation, where the question was my own struggle as to whether fashion merits being called an art form or not”. The beginning of the year, he reflected, had been particularly difficult and “at this moment, I find it more exciting to have abstract conversations with people and beauty than just say ‘I’m going to show a collection’. And what I love about this collection is that it’s not immediate. It’s very personal. It’s a balance between my personal obsessions—I live with Magdalene’s works and Shawanda’s works in my home; I study ceramics academically as something that stops me smoking too much late into the night.” Besides simply shopping from his designs, he fervently implored any Vogue readers to investigate their respective practices—and, incidentally, to watch Adam Curtis’s new documentary, Can’t Get You Out Of My Head, which he watched during the same week that Teller photographed the collection and he feels “raises a lot of interesting questions which I think can be related to all parts of the arts”. If there’s been any bonus to lockdown life, it’s that we all have a little more time on our hands to fill with newfound obsessions. Here are a few new ones to play with.

2 / 5

He worked with Dame Magdalene Odundo

British potter Dame Magdalene Odundo is a long-standing close friend of Anderson, and a woman who he admiringly describes as “one of the most important artists of the 20th century”. During one of last summer’s lockdown interludes, when we were permitted to see each other in our gardens, he had gone to spend some time at her studio in Kent to catch up. While talking about their respective work, she described one of her vessels as reminding her of Naomi Campbell, “the body and the curve” of it, Anderson recalls (he subsequently sent her an Alaïa monograph). “Usually we just talk about pots but, with all this time, we started talking about a broader viewpoint: her perspective on the physical form,” he explained—a sentiment which clearly resonated with his, and which has played a formative role in this collection.

She had also been working on some prints and he thought, rather than apply them to clothing, to consider them as tapestries and translate them into limited-edition blankets which could envelop the body. “If you’re in good form, you lie down on the sofa with a blanket, or if you’re sick you wrap a blanket around you. It’s this idea of protection, this idea of warmth,” he continued. “It was probably the easiest way for her to lend her voice without it being ceramic.” It hasn’t even been announced where they’ll be sold yet, and they’ve all essentially already been bagsied by collectors. Clearly, a good idea.

3 / 5

And Shawanda Corbett

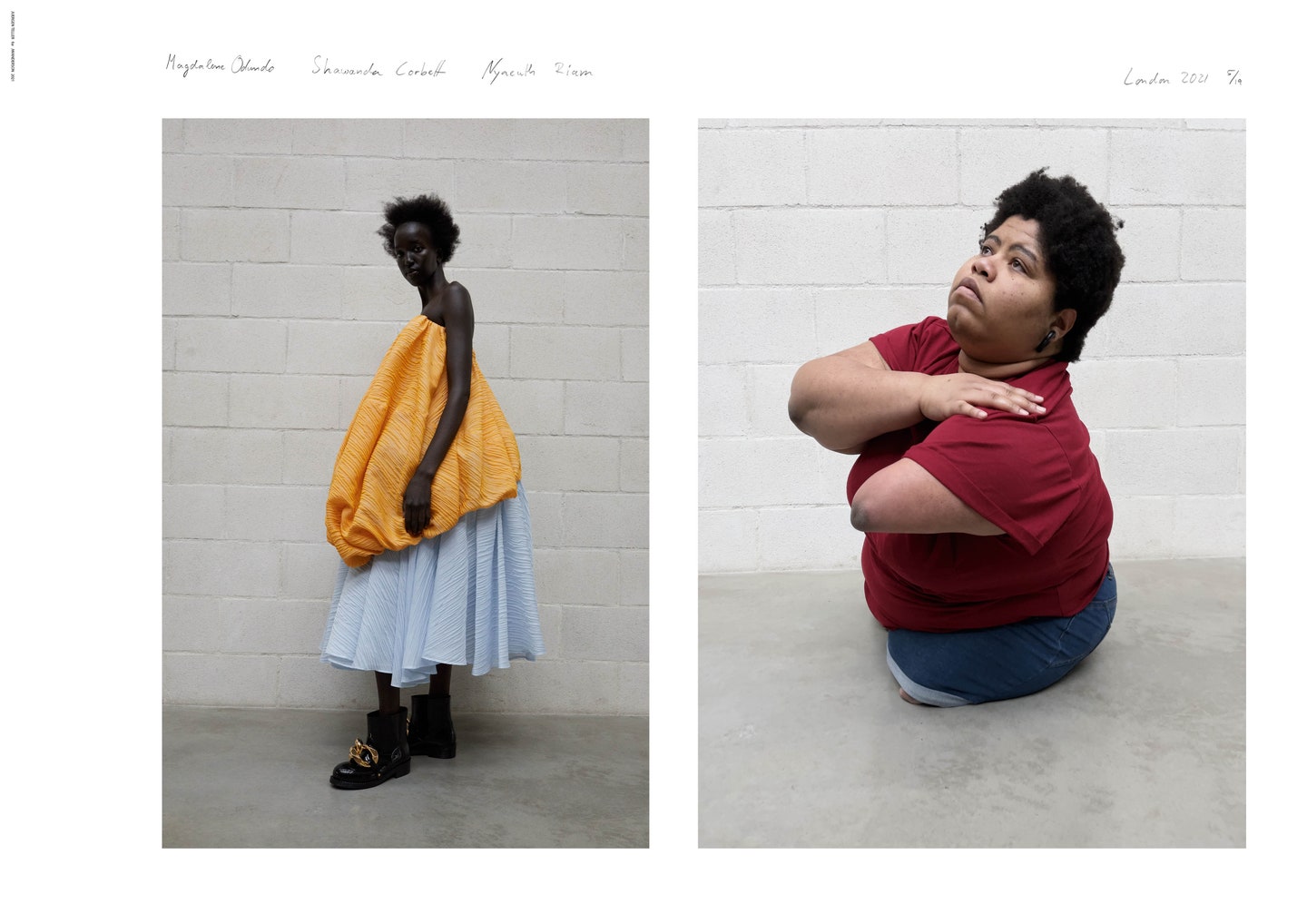

During another of those breaks in lockdown, Anderson managed to make it to London’s Corvi-Mora gallery to see a show by the young American artist Shawanda Corbett, who is currently based in the UK, and was entirely taken with her work. He mentioned his admiration of her to Magdalene, who he learned was similarly fascinated by her, and started a conversation with Corbett online where he learned she looked up to Magdalene. “I feel so lucky to have encountered these two artists, born continents and generations apart, both exploring the idea of the body and its physicality, and the notion of pots not just as physical vessels but also vessels of information,” he wrote in a lovely letter which accompanies Teller’s pictures. “It was incredible to feel the power and influence objects can have on you.” He wondered how he could engage them both in a cross-disciplinary dialogue about the body—and the collection somehow became the vessel for it, both through the blankets (Corbett also created three designs), and the pieces themselves. “I think the vessel, like clothing, is something very intimate,” he reflects. “It’s about wrapping, it’s about what you put in the vessel, it’s about the figure. I think that’s why I have such an affinity for ceramics, why I’ve been collecting them for 20 years: because they ultimately have something to do with the body.”

4 / 5

There was a variety of refined silhouettes

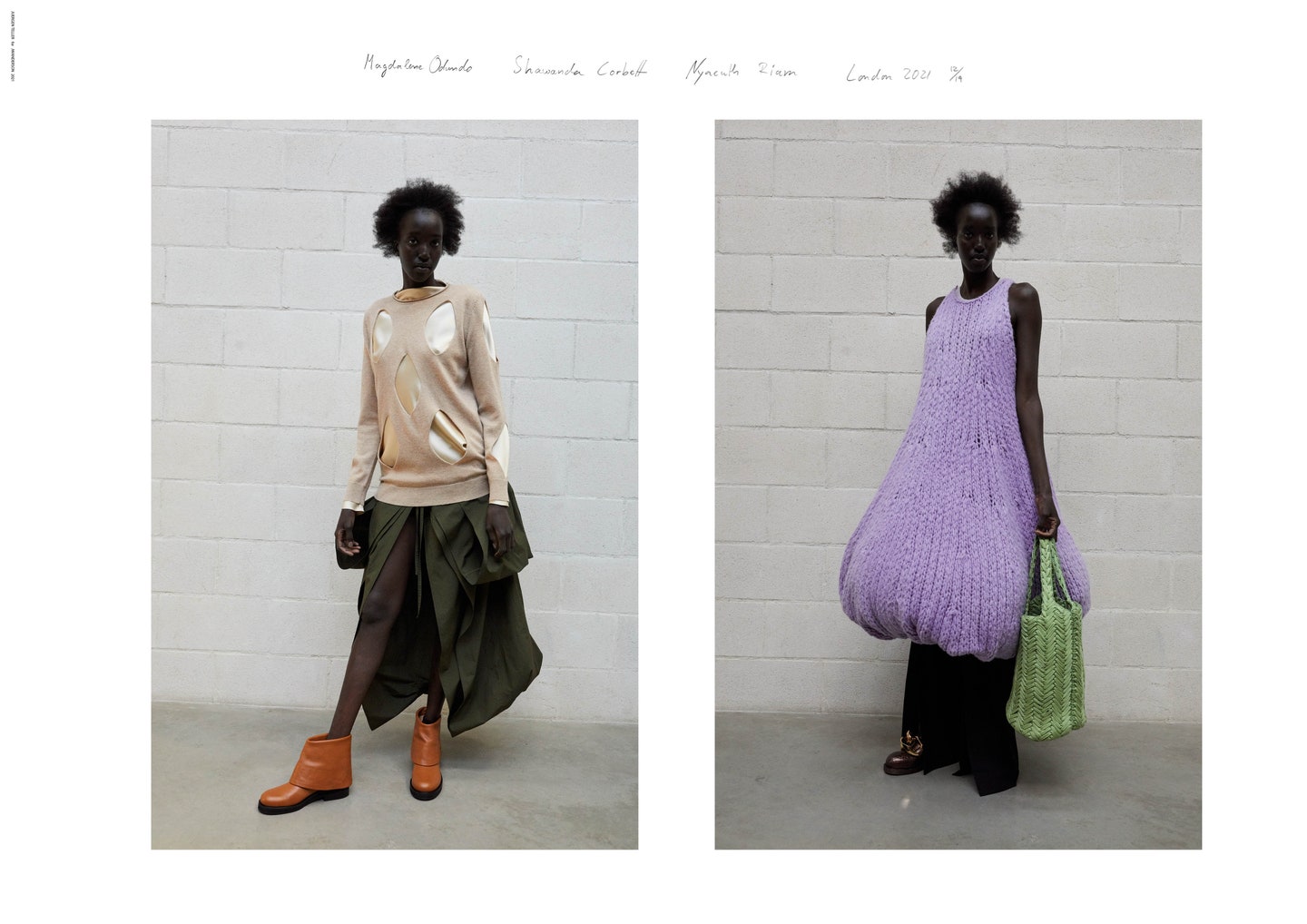

So: extensive preamble complete. What of the clothes? Their undulating forms pay direct tribute to the works of these two women: voluminous knit dresses inflated through interior netted tubing (which took nearly two months to articulate); draped fabrics cut so as to envelop the body; outerwear made somehow sculptural. You hardly need me to describe the comparisons; the array of pictures do that better justice. The collection comprises comparatively few looks—19 in total—and “I think it’s quite exciting, to kind of not be held to the peer pressure of performing 60 looks,” Anderson says. Over the past year, our monthly Zooms have been punctuated by our respective reflections on the industry’s adaptations to the pandemic: when, near the start, everyone decreed they’d dismantle the fashion calendar; when, later on, everyone seemed to do away with that idea; when regulations began to preclude conventional shows; when they loosened and everyone returned as quickly as possible to their usual machinations. The world has been upended, but fashion apparently refuses to shift very much in any new direction. “We all got used to the idea of fashion weeks, so we kept it and protected it even though fundamentally it wasn’t working,” he notes. “We have to, as a body of people who work in fashion, start thinking about how it cannot just go back to how it was. And if it does—then it will collapse.” Here was a gorgeously and concisely considered alternative: less, but better.

5 / 5

He revived designs from previous seasons

On that note—Anderson has also revived a bag from 2014, which didn’t particularly resonate with his audience at the time but, judging by Instagram, appears to hitting the mark now. “I mean, it did alright—but it wasn’t exactly a chain loafer,” he laughs, alluding to his smash-hit shoe which again grounds this collection. He still often thinks of this handbag because both Sarah Mower and his mother still carry it—and it made him think of all the ideas rendered redundant by the pace of this industry. “When you do a show, you pack in so much that you never end up seeing it all,” he explains. “It comes to the production edit, and suddenly there’s too many bags and half the collection gets thrown out the door and then, by the next season, you’re done with the idea so you move on.” Its appearance, then, appears more than just a timely revival—but a statement of intent.