In just two years between 1996 and 1998, photographer Glen Luchford collaborated with Miuccia Prada on a series of campaigns that are so era-defining it feels like they were created over the course of a decade. For Prada SS97, Amber Valletta—wearing a diaphanous brown dress and black shirt—floats serenely in a pool of water, surrounded by fog like a kind of grungy Ophelia. The following season, the model is seen in an embellished top staring through a peephole, transfixed by something—what we don’t know—as she paces through a snow-frosted maze, dressed in a black overcoat and trousers.

Part Stanley Kubrick, part Andrei Tarkovsky, Luchford has compiled these cinematic images into a book, his sixth, published by IDEA this week. Titled Glen Luchford Prada 96-98, the volume includes a later campaign inspired by the work of German dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch, which was never released. Together they represent a bygone age of fashion campaigns where products are merely props rather than the subject, in some cases barely visible, and the mood of a collection is distilled into a single look.

For all their dramatic qualities, Luchford insists he never had any intention of creating a narrative through the Prada photographs. As he explains in conversation with writer and curator Lou Stoppard in the book’s opening pages: “I just had films in my head and scenes that had always stuck with me, and I wanted to find a way to recreate them in a fashion context—it was nothing more complex or intellectual than that, it was pretty simplistic actually.”

Simple, but highly effective. And in a world that seems ever-more complicated, Glen Luchford Prada 96-98 is a welcome slice of 1990s nostalgia. Here, the photographer reflects on this chapter of his career and describes the future of fashion photography as he sees it.

What led you to publish these images as a book?

One of the reasons is that almost every day someone has tagged me in one of these pictures on Instagram. I realised that they were being circulated the whole time. Why? I’m honestly not sure. There’s something about them that people want to go back, revisit and keep looking at—through the lighting there’s a seductive quality, an atmosphere there. It was a winning combination where all the elements came together: right clothes, right model, right concept.

Did you ever anticipate how potent these images would become?

When everything comes together like that in one moment and the sparks fly on the set, you realise you’re on to something. It doesn’t happen that often, but when it does I guess you’re aware of it.

I didn’t have any expectations of those pictures beyond my other pictures. In fact, one of the things that I enjoy about fashion is that every month you’re on to something new. But their impact outside the fashion industry was surprising. Hollywood film directors and cinematographers reached out to me and said how much they’d loved them, and MoMA [in New York] included them in an exhibition.

Actors Joaquin Phoenix and Willem Dafoe also star in the campaigns—do you have any memories of working with them on set?

Joaquin was a bit shy given it was his first campaign, but his presence is so immense that it more than compensated for his shyness. I find most actors are like that in a stills environment [as opposed to moving images].

Willem I knew, as we’d worked together before. He’s very comfortable and giving on set—always a gentleman. We were shooting in a small apartment in Milan with just a few crew members, for two days, so we had a lot of fun.

Does your approach differ in any way when shooting an actor rather than a model—Amber Valletta, for instance?

Amber is a pro and knows that standing in the freezing cold for hours is an unfortunate byproduct of our job. With actors, you can’t necessarily do that—the trick is to get them away from any PRs, and make them feel comfortable and relaxed. So politically, it’s more tricky but the technique is the same.

You took a break from collaborating with Prada to work on your film Here to Where (2002) and came back a few years later to shoot the Pina Bausch-inspired campaign, which is a lot more kinetic. What inspired this change of direction?

In order to make the pictures the way that we did [from 1996 to 1998], we used long exposures. Amber had to stand completely still for every click of the camera so it creates this static way of working and it could be very frustrating. When I came back, I thought: ‘Now I’m going to do the opposite. I’m going to use completely different lighting and get as much movement in there as possible.’

From 2015 to 2020, you created some equally memorable campaigns with another hallowed Italian fashion house—Gucci. How does working with Miuccia Prada, your “patron” as you describe her, compare to Alessandro Michele?

There are similarities between Miuccia and Alessandro: they’re both intellectual, hilariously funny and charismatic. And they’re both creative people who think in a broad sense. They don’t just think in terms of fashion, you can discuss anything with them from literature to art to antique furniture.

The difference between the two was that with Miuccia, I worked with her very much as a collaboration where I would come up with ideas and take them to her. Whereas Alessandro is very much the creative director of Gucci. My job was to interpret his thoughts and ideas.

What do the Prada images represent to you today?

The book is a benchmark of the end of analogue and the beginning of digital. I started the project completely in analogue, and I finished it digitally so it was a monumental shift for me—a lot of other photographers didn’t adapt for quite a long time.

Digital photography changed us negatively in the sense that there was a lot of trust between the photographer, the art director and the designer. Once you were hired, you would share a Polaroid now and then, but you were trusted to deliver something that was going to be liked and left to get on with it. With digital, photography became a group sport—everyone crowds around the screen putting in their 10 cents. You have to sacrifice a lot of control—it’s a different system.

Where do you think photography will go from here?

Editorial hasn’t changed for the past hundred years. You’re commissioned by a magazine to shoot, say, 10 to 12 pictures. You plan it, shoot it, do the post-production and deliver it to the magazine. A month or two later, the magazine comes out.

It’s going to come to a point soon where you’re shooting the pictures on set, retouching them and then bang—they’re up on the magazine’s Instagram. There’s going to be another big shift where people are making decisions right there and then, on the spot. With TikTok, people just want to be entertained in 10 seconds and then move on.

Glen Luchford Prada 96-98 is published by Idea and is also available at Dover Street Market

1 / 5

Prada SS 1997 Amber Valletta

2 / 5

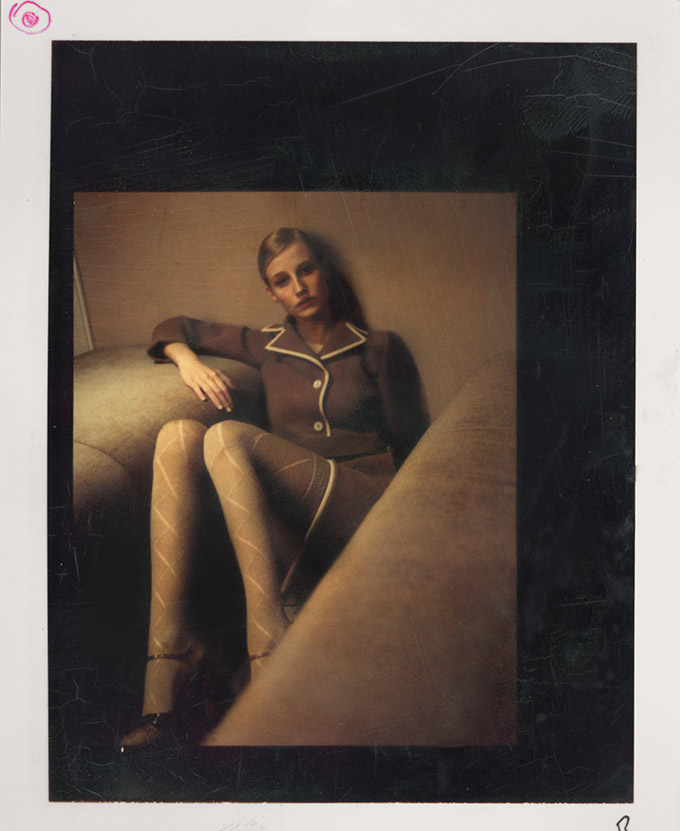

Prada AW 1997 Norman Reedus

3 / 5

Unpublished image from Pina Bausch Dancers Project 1

4 / 5

Unpublished image from Pina Bausch Dancers Project 2

5 / 5