Trigger Warning: This story contains mentions of disordered eating, and may be disturbing for some. Reader discretion is advised.

Two years ago, Cherie went through a long period of what she calls her “dark night of the soul.” She was a musician who played guitar in a few different bands, but she felt aimless, like life had no meaning. “I was trapped in this box,” she says. “Stepping out of that box that I had locked myself into–that was how I found Slimy Oddity.”

Cherie was doodling one day when she stumbled upon the formless, colourful blobs that she uses as characters for her online art under the banner of “Slimy Oddity.” The captions, written by her husband, Tim, offer spiritual tidbits of advice and existential pick-me-ups. “Slimy Oddity was really what saved me at that point in my life,” the Singaporean artist, who turns 30 this year, says. Slimy Oddity now has more than 150,000 followers on Instagram, and Cherie creates for it, drawing and collaborating with brands like Casetify, full time. “It gave me a renewed sense of purpose. I’m able to transmute my experiences and translate the lessons I’ve learned into these joyful pieces of art.”

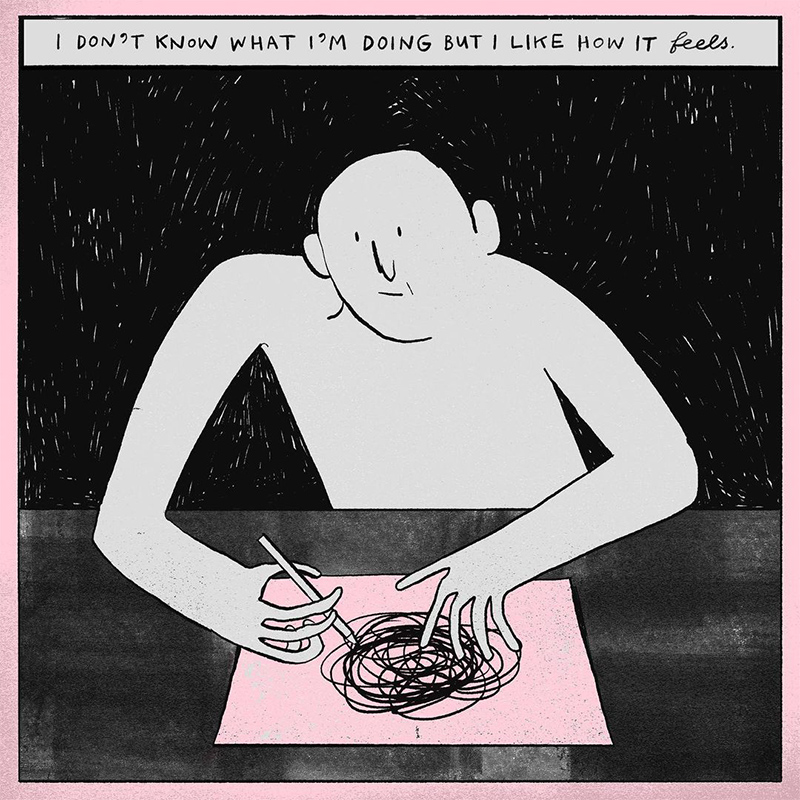

Priyaa, who goes by the moniker “inkipri” online, is another local artist who emerged from an existential crisis by drawing her way out. Illustrating had always been a hobby, but her habit went into overdrive in 2018, when she coped with going through “a rough patch” by drawing upwards of five hours a day. “I was pulling all-nighters just to journal,” Priyaa, a student now awaiting her A-level results, says. “It was quite intense. It was something I had to do, for myself. It became a coping mechanism. And it was only at that point of time that I actually developed my style, the way I draw. Right now, it’s just something I thoroughly enjoy. A way to express myself, basically.”

That expression—the abstract, jagged way she puts pen to paper—clearly resonates with her audience. They often message her on Tumblr or Instagram, telling her that her art, or the wrenching, implosive captions she writes to accompany it, makes them smile or feel less alone. Some of them have gotten her drawings inked onto their skin; that blows her mind. The community that she’s built feels like a safe space and a group hug. “It’s an honour to be a small part of so many strangers’ lives,” she says. “When people tell me how much a piece resonates with them, it reminds me of how… the human experience is more unified than we can possibly fathom.”

This art, whether you want to call it drawing, illustration, or cartooning, vibes along a very specific wavelength of that human experience. But the doodles themselves vary widely in style and message, according to each individual artist. They can be angsty, furious, anxious, uplifting, or sweet. It feels like they were drawn and posted from a quiet bedroom at 3am. They live, as creations, almost entirely online. They often use nature or outer space for settings, and blobby shapes for characters, which act as stand-ins for the artist’s own messy feelings and depersonalised sense of self. They’re a part of the 21st century canon of existential yearning behind something like The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, as well as more recent phenomena like remixing Toto’s “Africa” to sound like it’s playing in an empty mall.

Most importantly, they’re more felt than seen, putting squiggly lines and short captions to ascribe meaning to universal, inarticulable human feelings. They’re loose hieroglyphs for the digital age, swimming through the aching nostalgia, vain hope, and surreal dread that comes with being a member of the millennial or Gen Z generations.

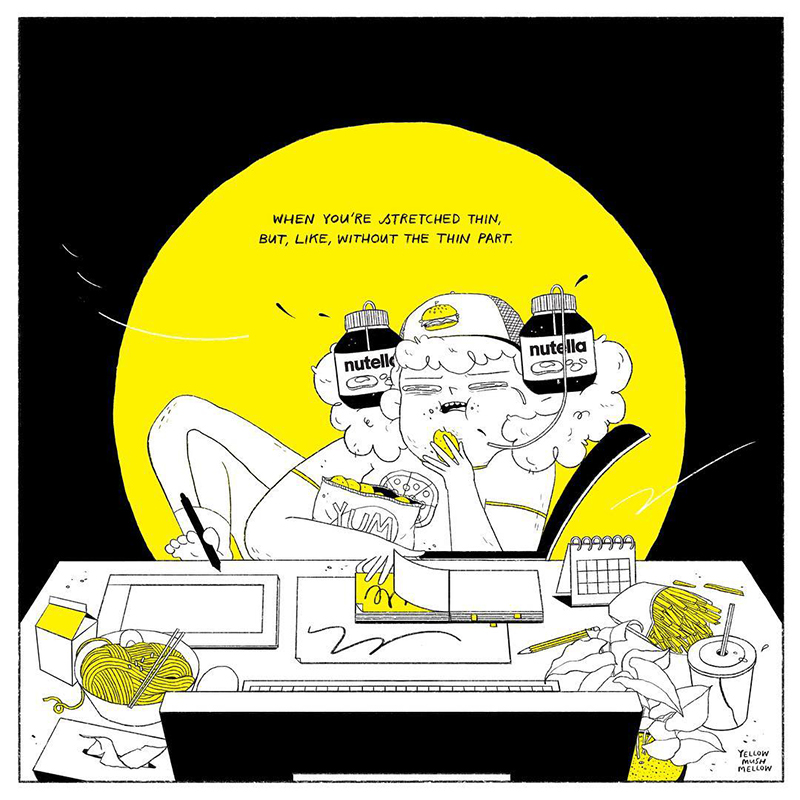

Aida, who is 27, floats in the nebulous void between those generations. She went from doodling comics at the edges of her test papers (“Death By Exam,” the series was informally called) to studying art formally in university to working in advertising. Throughout it all, though, she’s always had the itch to just make art for fun. From that desire, she created “Yellow Mushmellow,” posting comics and illustrations about her daily life to Instagram.

She uses her art to look at life from a different, lighter perspective, channelling her fears and frustrations directly into her work. She often draws about her own mental health journey, for example. “I have this series of comics about this girl who’s always binge eating,” Aida says. “Basically, when I’m sad, I’ll eat a lot. It’s temporary relief, and then guilt. Then I’ll draw the girl, which I guess is my way of processing all of that. It’s cathartic.”

Aida’s drawings are highly personal to her own experience, but they’re vulnerable and open enough that thousands of people look at them and think to themselves, “Yeah—me, too.” She’ll ask her followers what makes them happy, or how they’d like to die, and dozens of responses will flood in. If her art is a call into the digital void, then the shouts she hears back are just as exposed and raw as her own.

She then incorporates their ideas into her projects. Her favourite project involved asking people what silly things their families did during Hari Raya, and turning their answers into a pattern for a baju kurung. Her audience’s thoughts can break through the screen and make it into the physical world, too. A few years ago, the Hospice Association of Singapore approached Aida with a commission to paint a mural on a wall, to create a conversation about death (hence the query to her audience). “Death is taboo. I could paint a mural and call it a day. But if you really want to have a conversation—then let’s ask people about it. That’s how I started.” People messaged her that they wanted to die surrounded by flowers, or next to their favourite cat. She put them all into the mural. It really brightened up the space.

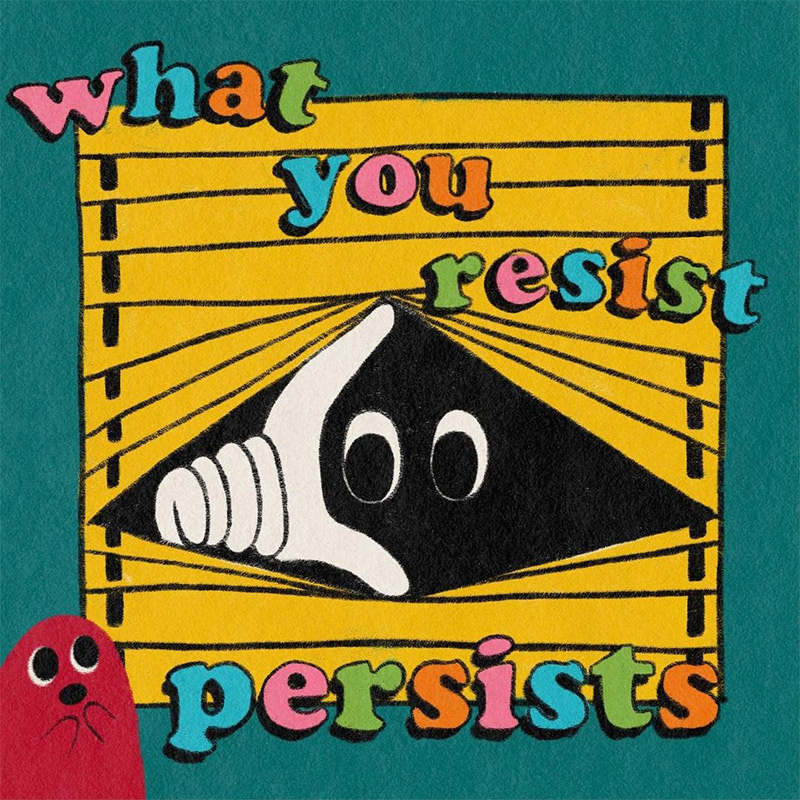

Vulnerability begets vulnerability, with this kind of art. The conversation that Priyaa has with her own audience is no less unguarded. Ironically, though, she protected her online identity fiercely for the first few years of its existence, unwilling to let anyone who knew her see her art. “Putting myself out there, it’s not something I’m inclined to do,” she explains.

A natural introvert, her anonymity was sacred, especially when she was sharing her innermost thoughts and feelings. An audience of tens of thousands was one thing, but someone at school, who could put a face to her name? “It’s way easier to be vulnerable with people you don’t know. It’s a very specific kind of relationship I have with [my followers] where they’ll share a secret with me, and I share my own experiences back. That relationship is built solely on being vulnerable, that human connection. Nothing else is tied to it.”

There’s often an intangible wish to go back to a happier, simpler time present in this kind of work, too. Cherie’s art is equally inspired by Sesame Street and its subversions, like the surreal web series “Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared.” “My inner child is pretty strong,” she says. “It just feels natural for me to express that, whether it be by dancing or drawing.” But she extrapolates it out—what can she, and her audience, learn from getting in touch with their childhood selves?

“I see Slimy Oddity as a bridge,” Cherie says, “for someone who is not as in touch with their spiritual side. It’s the simplest way to get a message across, to teach them. The colours, the shapes, the words—there’s an accessibility to the simplicity, that makes it very palatable. Anybody can digest it easily.”

The messages are so universal that they are coaxed out of the digital world and into reality, as in Aida’s mural. Both Cherie and Priyaa sell their illustrations as merch, screened onto phone cases and tote bags and t-shirts. When Priyaa launched her site and e-store last December, that was the first time what she was doing truly felt like it had actual, tangible weight. “I will never forget that moment. There were a couple hundred people just waiting, who just streamed onto the site,” she says. “That was the exact moment I felt like people actually do care for my work in the real world, and not just on a screen. Because sometimes social media can feel so fickle.”

The impermanence of social media is part of what makes Aida feel like she might not be doing what she’s doing forever. “Maybe next time I won’t be an artist,” she says. “I will change my job. But I feel like I’ll never lose that—that itchiness, you know? To make something else of the everyday.”