Instead of sitting amid the high-vaulted, light-drenched glamour of the Fendi ateliers to talk with Kim Jones about his first collection for the Roman house, we go for a country walk in Sussex on an awfully grey day prior to lockdown, blustery and bleak with thick mists rendering it almost dark in mid-afternoon. We’re a long way from the Italian capital, where scores of seamstresses are in the process of weaving lattices of pearls and ornately embroidering couture gowns for his upcoming debut, but, nonetheless, it soon makes a lovely sort of sense. Jones recently bought a holiday home here, in the quiet village of Rodmell—a stone’s throw from the house where he spent much of his upbringing, and a few doors down from Virginia Woolf’s cottage—and he’s brought me here to give me a tour of his childhood. “As a teenager, I spent a lot of time cycling round all these villages,” he smiles, sidestepping a growling tractor. “This first collection feels almost autobiographical. What I’m referencing feels really personal.”

While this is Jones’s first womenswear collection, he has stood at the forefront of fashion for more than a decade: his, thus far, three-year tenure as artistic director of menswear at Dior—where he has translated the feminine romance of the founder’s codes into elegant tailoring and a boldly contemporary sensibility—has already earned him almost every industry award going (alongside a wealth of female fans, from Bella Hadid to Naomi Campbell). Before that, his seven years as director of menswear at Louis Vuitton are regularly credited with transforming the fashion landscape by transposing his encyclopaedic knowledge of streetwear’s cultural codes on to hyper-luxurious terrain. (In 2017, he was responsible for the house’s collaboration with Supreme, broadly considered a signifier of fashion’s shift into a new age.) Accordingly, much has been written about his youth: the son of a hydrogeologist who specialised in irrigation projects, Jones grew up between England and Africa (with stints in Kenya, Ethiopia, Botswana, Tanzania and Ecuador), and his early life is easily mapped on to a lifetime of collections imbued with wanderlust and disparate cultural references. “From a small age, I realised there was a lot in the world to see,” he says. “But in many ways, it’s harder to research in lockdown, so what I’ve done is look internally.”

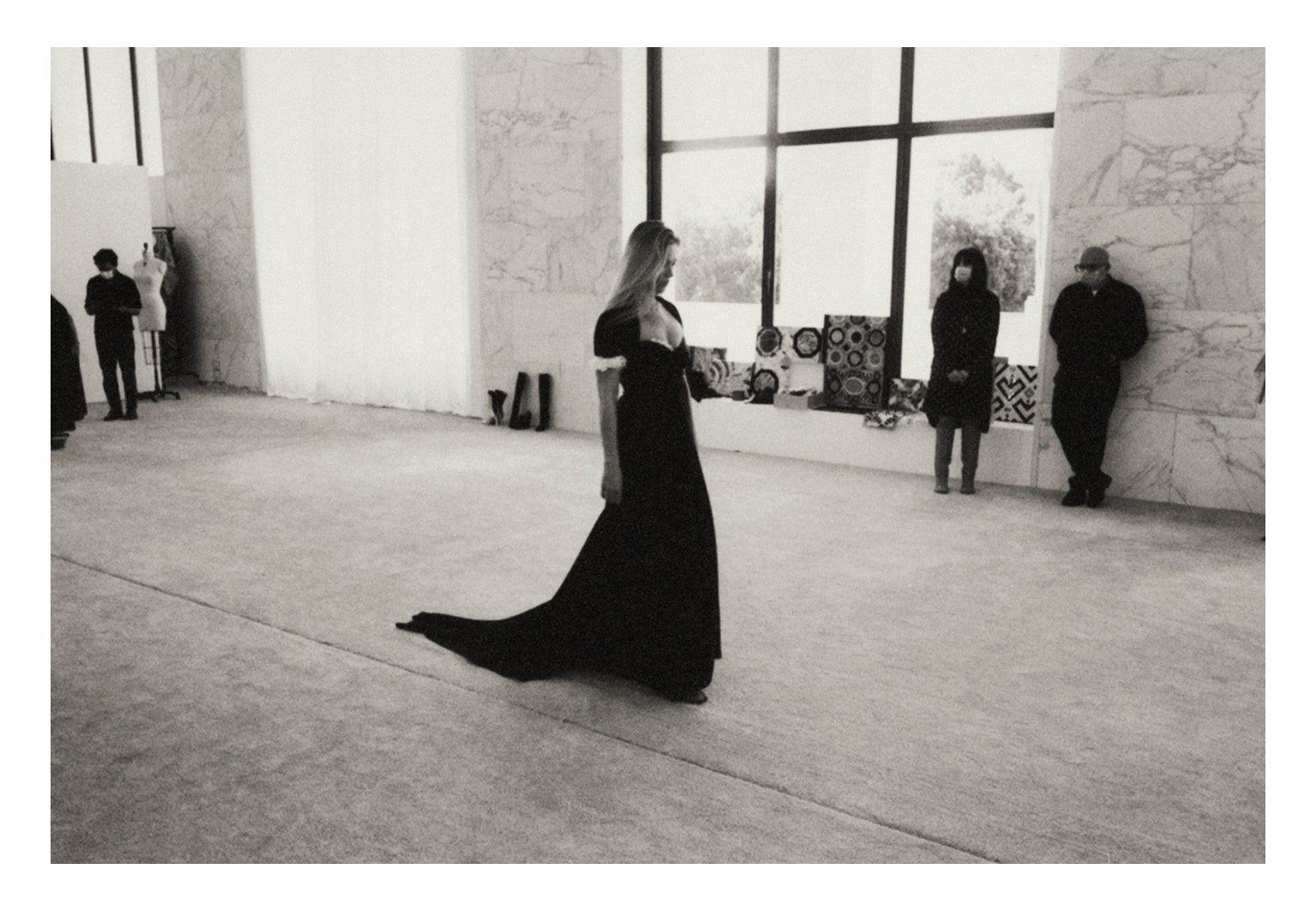

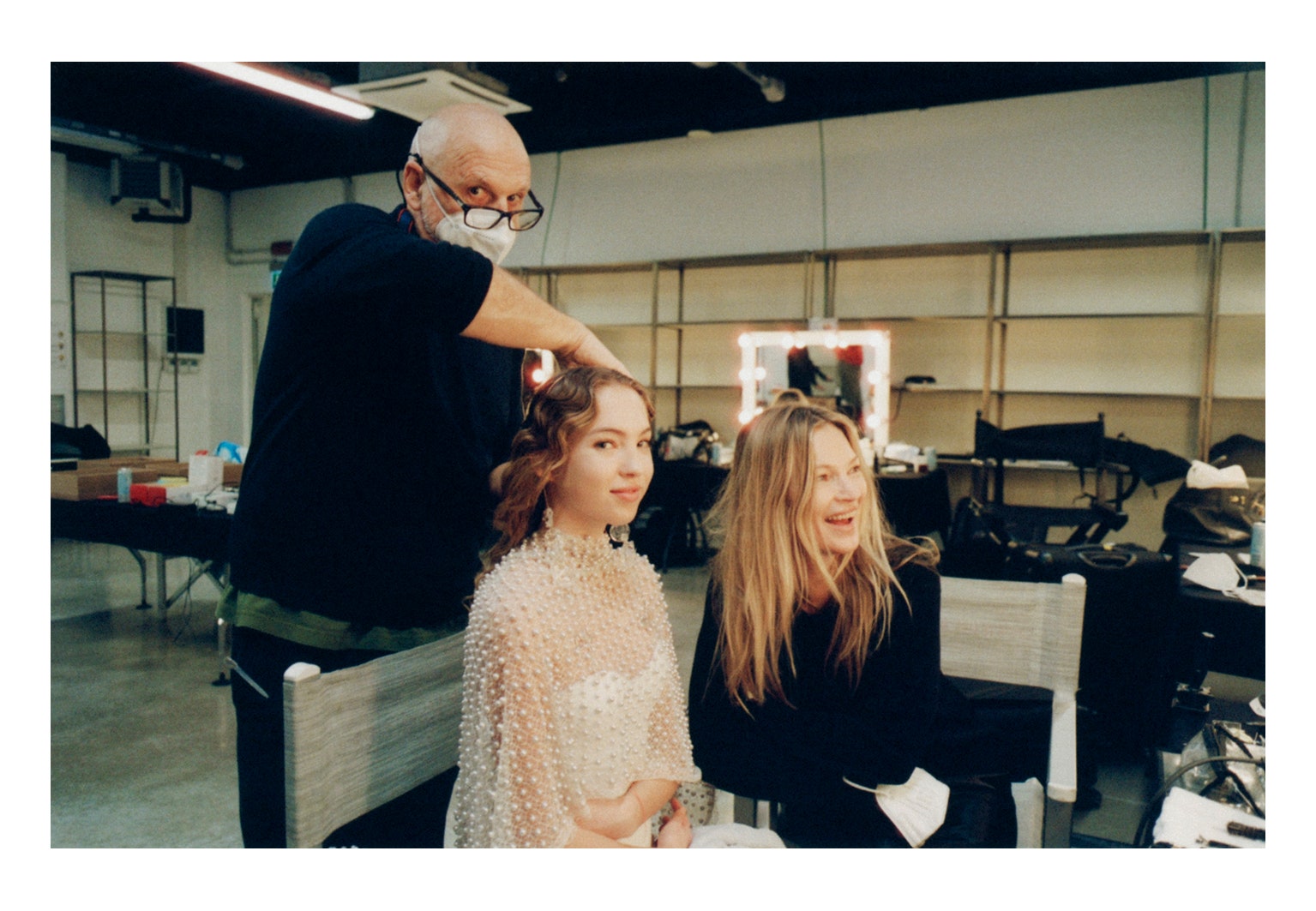

Rather than commandeering one of his regular research trips to the Amazon or Japan, for Fendi, Jones has returned to the youth he spent here, in Rodmell, around Lewes and at Charleston farmhouse, where he’d go sketching after school in the bucolic gardens or etch lino prints from the Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell frescoes on the walls. It is here that, one December afternoon, as rain spits against the painted windows, Kate Moss is lounging upon the same living-room chaise as the Bloomsbury set would have nearly a century ago, while dressed in Jones’s newest designs. (Moss is also consulting on accessories for Fendi. “It was logical. She has such immaculate taste—she’s seen everything, and her knowledge of fashion is so vast,” says Jones, who has known the model since Lee McQueen introduced them in the ’90s.)

“I always wanted to wear his menswear—and now he’s making womenswear!” Kate laughs, draping a dress that hybridises crisp grey masculine tailoring with a gown embellished with hundreds of crystal wildflowers. “What he does is always very cool and modern. He knows exactly what people want to wear.”

Later, I ask Jones what could possibly have drawn a teenager to this curious little farmhouse, with its low 16th-century ceilings and its perfectly preserved bohemia. “When towns have a famous literary or artistic figure who lived there, it’s in the air,” he recalls. “I’d always see the old bookshops in Lewes with Virginia Woolfs in the window. Old school essays I’ve found were written on Roger Fry. They were ever-present.” There was something about the collective creativity of the Bloomsbury set—immortalised by Charleston, where they worked and romanced one another with remarkably liberal attitudes—that he says was irrepressibly magnetic. “I thought that a group of people coming to live together in the middle of the countryside at that time was quite forward-thinking. They were like a posh commune,” he laughs. “And their cast on what was happening at the time was impressive and wide. The forward-thinking of John Maynard Keynes’s economics and Virginia Woolf’s books, like Orlando.”

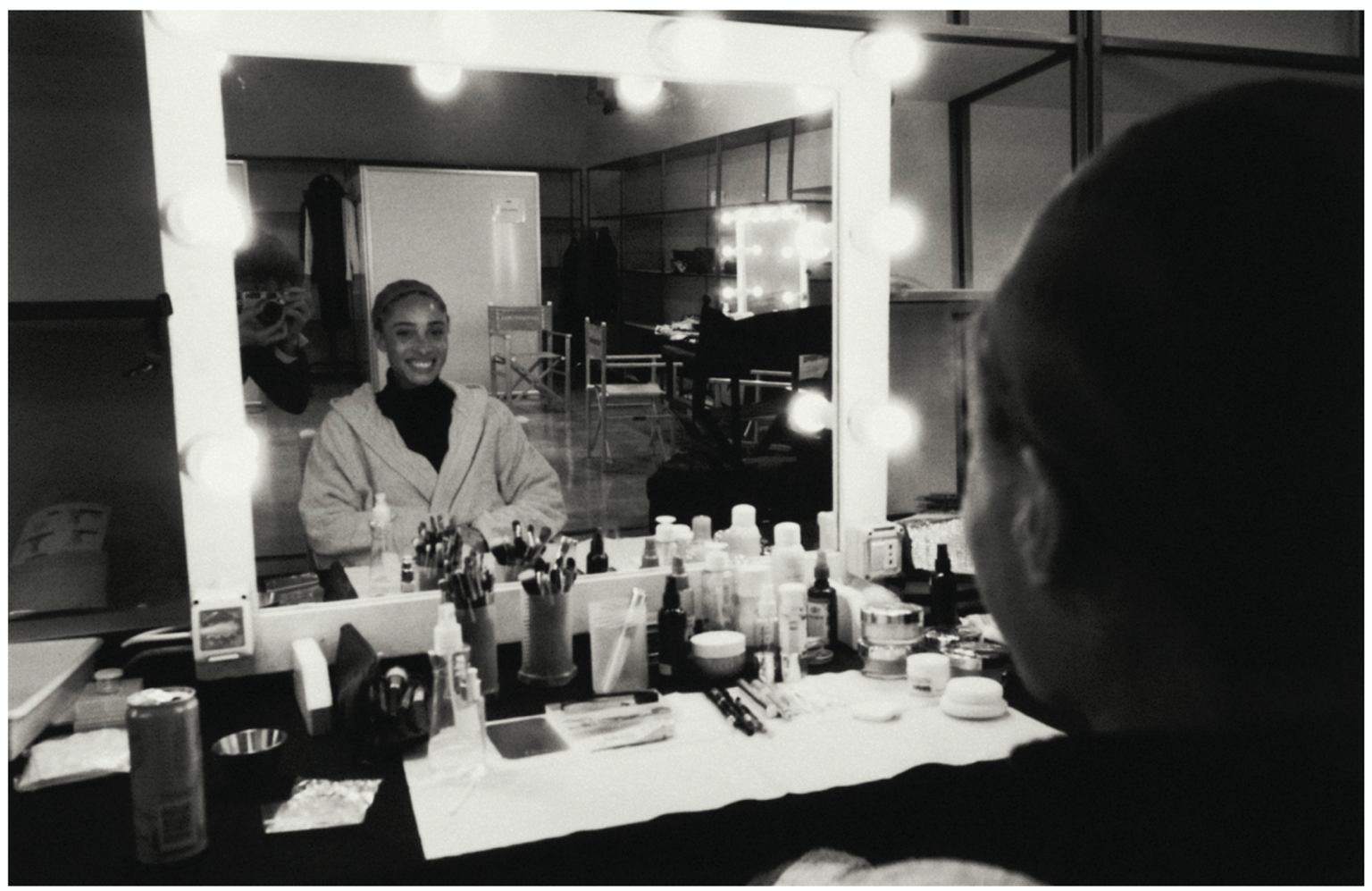

The collective energy of the movement is distinctly visible in the way that Jones operates now. “It was collaborative, a family,” he says of the group. “Which is how I like to work.” He is renowned for his collaborative spirit, both with his teams and his extensive circle of illustrious friends (from Kanye to the Beckhams, Kate to Naomi, his dinner-party placements are a brilliant blend of global A-listers and Sussex school friends). “What I love most about Kim is his ability to bring family wherever he goes,” reflects Adwoa Aboah, one of the formative muses for his vision. “He keeps such a wide range of people around him—artists, musicians, the youth, everyone—which is why his work continues to remain so relevant. He finds inspiration everywhere.” (Jones proudly knows as much about Baby Yoda as he does about Woolf, and he prizes his Julien Macdonald hamburger boxes as highly as his art collection; he’s not one for cultural snobbishness.) That energy is pronounced in his debut, which will be modelled by families both chosen and biological, but it is Orlando, Woolf’s modernist novel, that has offered the most direct starting point for his couture collection. A time-travelling exploration of the mutability of gender, it was written in dedication to Vita Sackville-West, Woolf’s long-time paramour, whose son later referred to it as “the longest and most charming love letter in literature, in which [Virginia] explores Vita, weaves her in and out of the centuries, tosses her from one sex to the other, plays with her, dresses her in furs, lace and emeralds, teases her, flirts with her, drops a veil of mist around her”.

The story has been regularly referred to in fashion—its explicit references to the importance of clothing in establishing one’s identity easily lend themselves to designers looking to imbue their work with meaning—but Jones has taken a more oblique approach in reasserting its relevance. Just as Orlando oscillated between the worlds and wardrobes of different times, Jones has used the biographies of the women who will model his debut to excavate the Fendi archive, drawing references from their respective years of birth and the house’s history. “Each look is about the personality who will be in it. That’s the luxury of couture, it’s designed specifically for the person,” he says. (“It feels like an authentic representation of who you are. Nobody ever asks me what I like,” laughs Aboah, whose outfit for the show evolved from a 1990 Karl Lagerfeld sketch for the house.) “I wanted to look at different points of time in Fendi—which is why Orlando came into my head. I wanted to pull out points of reference from Karl, but renew them,” Jones continues. “To look at them in a lighter way, to see them with a new eye, but without it appearing nostalgic.”

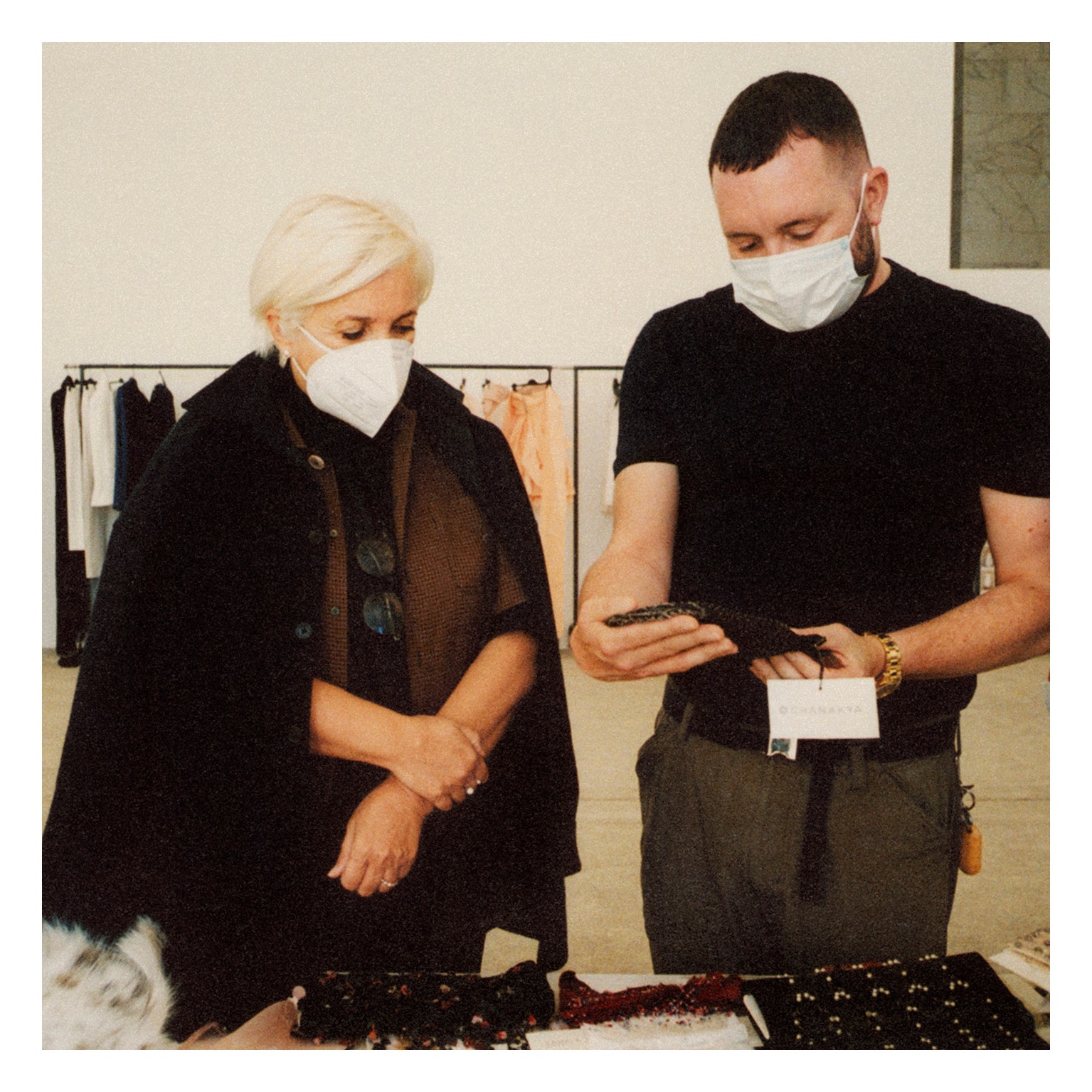

Equally, Woolf’s staunch feminism—and the Bloomsbury women, each a force in her own right—offer a parallel, he suggests, to Fendi’s history as a matriarchy. While Lagerfeld served as creative director at the house for the 54 years up until his death in 2019, its name has been upheld by the four generations of women who have acted as its custodians since it was founded in 1925 by Adele Casagrande (who named it in honour of her husband, Edoardo Fendi) – and it was Casagrande’s five daughters who, in 1965, recruited the German designer to modernise the brand’s aesthetic. In the interim between Lagerfeld’s passing and Jones’s debut, Silvia Venturini Fendi—Casagrande’s granddaughter, who has directed the brand’s menswear and accessories since 1994—acted as its creative guardian before handing the reins to Jones. “I always had an attraction to Kim—and now that I work with him, I understand why,” reflects Silvia, who has considered the designer a friend for more than a decade, and still remains an integral part of the brand’s creative process. “I am very happy—I like working as a duo, and working with him reminds me a lot of how I used to work with Karl. This was written in the stars. It was karma,” she says. “I really admire her,” Jones says on set while sending an enthusiastic stream of messages to Silvia. “I want to make her proud.”

What he has created for his debut, then, is something of an amalgam of Jones’s own lifelong obsession with Bloomsbury’s profoundly British romance and the historic Italian grandeur of the Fendi name. “What’s been particularly interesting to me, while spending more time in Rome, is that I’ve seen more of the huge amount of references that the Bloomsbury Group took from there,” he notes (later, to prove his point, he pulls out a catalogue of Vanessa Bell’s paintings, which flit between Sussex farmland and the Borghese gardens in Rome; Woolf was also particularly taken by the “infinite silence” of Perugino’s frescoes; and in London, Fry would hold exhibitions and translate his own understandings of Italian Old Masters). “And if you look in the Charleston library, or at Clive Bell’s book collection, it’s all there. All roads lead to Rome.”

In the collection, déshabillé draped dresses are cut as if frozen in time in the manner of Bernini’s marbles, but are hand-embroidered with wildflowers; swirling swags of fabric are affixed by blooming rosettes. He has found echoes of Italy in the marbled paper that once bound Bloomsbury books, which the couture ateliers have now translated into a wealth of breathtaking fabric techniques. The tragic story of Woolf’s suicide (a substantial part of our walk is spent tracing her final footsteps to the river in which, aged 59, she drowned herself) is echoed in pooling gowns dripping with crystals, or bulbous droplets of Murano glass strung as jewellery or inset as curlicue hairpieces. It’s exquisitely opulent, but rather than appearing abstractly ethereal – perhaps aside from a liquid organza gown that floats almost lighter than air, anchored only by its crystalline hem—it appears determinedly grounded in Jones’s world of cool covetability (Kate sitting at a table, slouched in an immaculately tailored satin suit proves the point). “We live in a modern world, so I like for there to be reality,” he asserts. Incidentally, nobody put it better than Victoria Beckham: “Kim is in touch with popular culture—and when you marry that with his incredible vision and exquisite craftsmanship it makes him a real force to be reckoned with.” Aboah agrees, “I’m excited because I know he looks at what you wear, what I wear—he’s continuously looking at everyone, at everything, and he wants to make clothes that women want to wear. I’m excited to put on those outfits, and feel epic in them. Because he’s more than capable.”

Once we’ve driven back from Sussex to Jones’s London home, he continues to give me a tour of the Bloomsbury artefacts he’s collected over the years. A gargantuan brutalist bunker in Notting Hill, with a swimming pool for morning workouts, a giant steel kitchen equipped for Sunday roasts, and walls filled with pieces to rival many museum collections, it is a well-insulated sanctuary from the outside world (when in London, Jones is a determined homebody), and its polished concrete surrounds have become the perfect backdrop to highlight his fixation with the collective. Here, alongside the art he has amassed over the years—Magritte, Francis Bacon, Amoako Boafo—there is a dresser painted by Vanessa Bell, which sat in Virginia Woolf’s Richmond home; Duncan Grant works hang in the living room; a Roger Fry folding screen mentioned in Brideshead Revisited; an endless library filled with first editions, publisher manuscripts and annotated copies of books that belonged to the Bloomsbury clan. “I’m obsessive,” he laughs. “I find it so exciting that you can buy these things—especially the books which people gave to each other. That these books have touched their hand, and the hand of the person who they loved and wanted to give it to… it just feels like there’s an energy to it. And you don’t ever really own anything; you’re just keeping it while you’re here.”

It’s a sentiment that echoes Silvia’s feelings about why Kim makes such a perfect fit for the house that bears her name: one that she says she loves more than herself for the weight it holds for her family. “One of the first things that Kim did was ask Delfina [Delettrez, Silvia’s daughter] to join us, which was the best thing—because it was a sign of love, and that he understood Fendi, and that its history goes on,” she smiles. “The first thing I wanted was to make sure Delfina came on board—because she’s the next generation of the family,” he continues (Delfina, whose eponymous jewellery brand has been thriving for more than a decade, now oversees the jewellery for the house). “I want to respect Silvia, and to think about the legacy of the house. Fendi is about them: about strong women, intelligent women, who know what they’re doing in their lives. Pioneering women, like the Bloomsbury women, like the women in the show. This is a statement: one to celebrate Fendi, and the stories of all of these amazing women.” It’s certainly a celebration—and the new chapter of the story will unfold from here.

This article was originally published on British Vogue