When Evan Peters took home a Golden Globe in January for his portrayal of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer in the Netflix series Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, Shirley Hughes—whose son Tony Hughes was among Dahmer’s victims—slammed the awarding body’s decision to present him the accolade. Rewarding actors for playing real-life serial killers, she pointed out, fed society’s obsession with true crime. Meanwhile, there was no acknowledgement of the victims or their families in Peters’s acceptance speech.

Although Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story attempts to set itself apart from typical true crime biopics by constructing its narrative from the perspective of the victims, Hughes and other victims’ families have spoken out about not having been consulted about the series. In turning their tragedy into casual binge-watch material, the show has reduced real victims into narrative tools and forced their families to relive the pain of the incident—all while profiting off of their trauma.

Still, that hasn’t stopped Monster from being renewed as an anthology—with two further chapters based on the lives of “other monstrous figures” to be revealed. After all, we seem to be in the age of the biopic. From Blonde to Elvis and I Wanna Dance with Somebody to Monster, last year’s on-screen line-up was saturated with biographical depictions of famous faces. And yet, controversy surrounding the genre is at an all-time high.

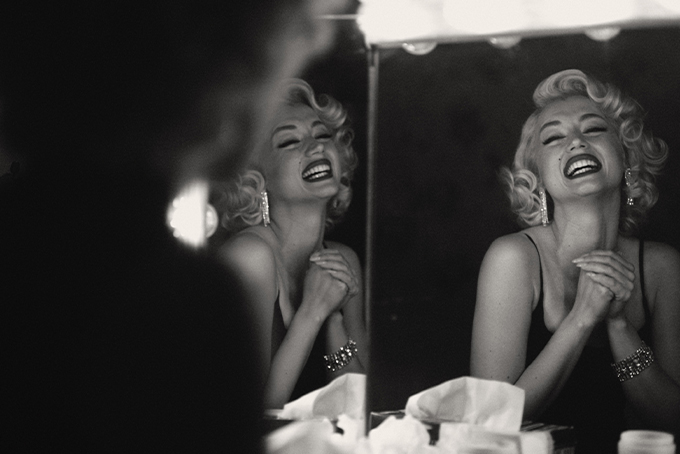

While a biopic can be based on any point in the life of a real person, the nature of the genre invites a significant portion of works to dive into downfall and calamity. Dramatising real-life tragedy is a slippery slope—one that easily slides into the realm of exploitation. Blonde, despite being marketed as a Marilyn Monroe biopic, seems to have no genuine interest in portraying the late actress as a complete person. A fictionalisation of Monroe’s life, it graphically strings together the most devastating misfortunes she experienced—from her abusive mother to multiple speculated abortions and various sexual assaults—which ultimately resulted in her taking her own life at the age of 36.

Described as a movie “about a person who is going to be killing themselves” by director Andrew Dominik, Blonde is just one film in a long line of narratives that seem to exploit female suffering. Its biggest focus appears to be on putting Monroe through as much pain as possible—sensationalising her trauma for all to see. In spite of this, lead actress Ana de Armas garnered an Oscar nomination for Best Actress in a Leading Role for her performance in the film.

Back to Black, the upcoming film based on the life of Amy Winehouse, has already received backlash for capitalising on the late singer’s trauma—especially after on-set images revealed a scene portraying her in hysterics at her husband’s arrest. Having passed away in 2011 from accidental alcohol poisoning at the age of 27, Winehouse’s early death and widely-covered struggle with alcohol and substance abuse has turned her into somewhat of a tragic symbol in the media.

Perhaps the most important question to ask when it comes to the genre is why a particular biopic is being created in the first place. Is the film meant to honour someone, or is it just Oscar-bait? Does it paint a decently accurate and well-rounded picture of the person, or does it just profit off of their suffering? A good biopic, first and foremost, is a respectful one.

There are plenty of other aspects of Marilyn Monroe’s life that a biopic about her could include, for instance. In a time of heightened racism, she spoke out against segregation. She was critical of the anti-Communist witch-hunts in the 1950s, and showed her support for the then-growing civil rights movement. Determined to oppose the sexist expectations of entertainment and media, she was also one of the first women to start her own production company. Rather than focusing solely on her misfortunes, sharing the accomplishments she achieved and causes she fought for is the least a film could do to afford her the respect she deserves.

We’re not looking for a perfect biopic—we’re just asking for one that doesn’t exploit the trauma of real people. And if a film struggles to meet that basic expectation, then it’s perhaps best to reconsider whether it should be made at all.