“Sticks and stones will break my bones, but words will never hurt me,” I remember saying as a seven-year-old to the other kids at school when they would make fun of me or tell me to “go back to China.” Often they were real bullies, but sometimes it was actual ‘friends’ who, not knowing any better, would ask me if I ate dogs as they pulled their eyes to a slant on each side with their hands.

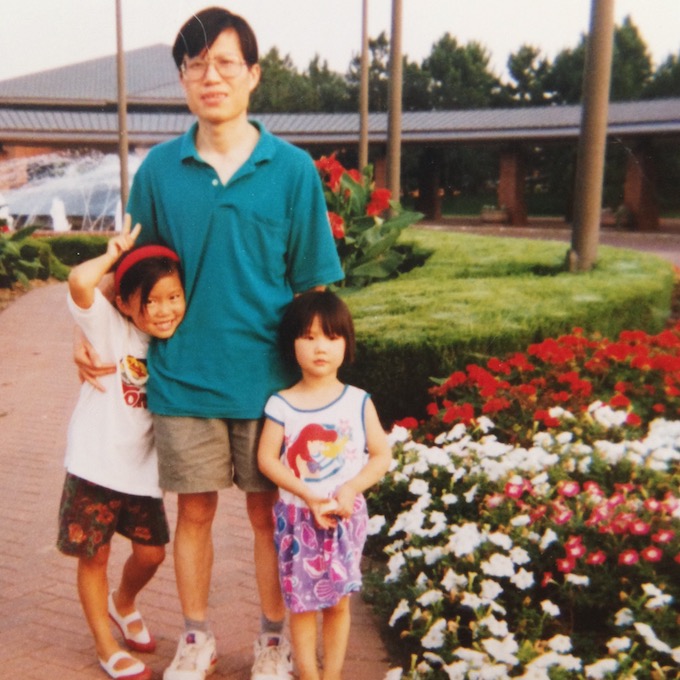

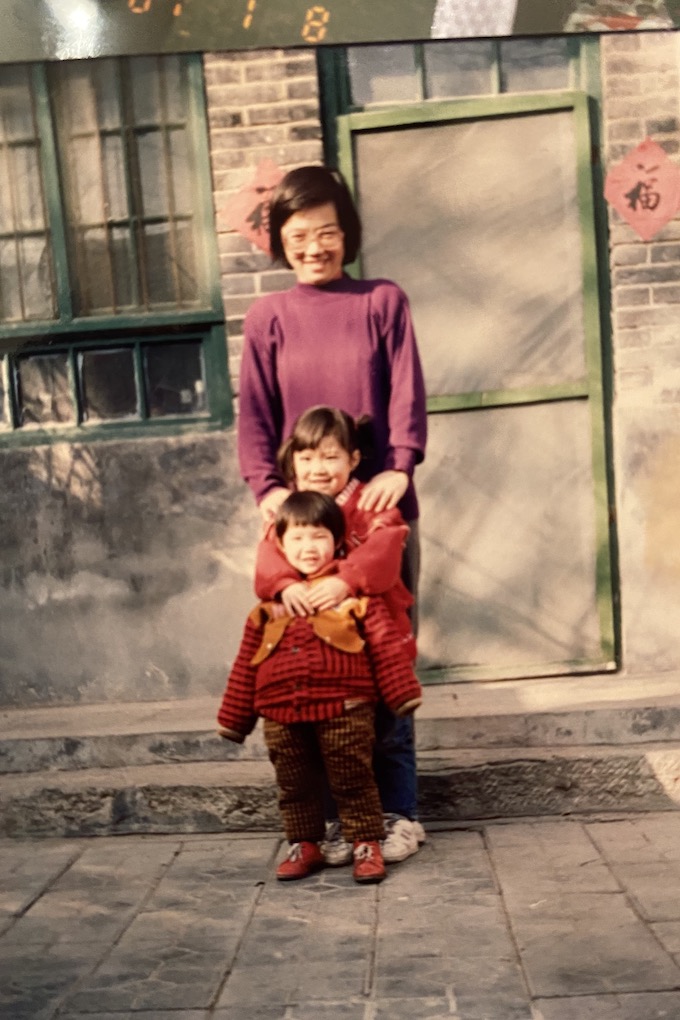

As a kid, I needed this saying. I was born in Minnesota, US, but lived with my grandparents in the province of Shandong, China, between the ages of two and four. I came back to Minnesota right before pre-school, not remembering a lick of English. My parents considered holding me back a year as my English was so limited, having to relearn my ABCs as a four-year-old. I remember staying silent more often than not to guarantee that I wouldn’t make a mistake or speak with an accent when attempting this new language. I made a vow to myself that the words of others would never hurt me, even if I didn’t fully understand the insult at such a young age.

COVID-19 has magnified the prevalence of anti-Asian racism

But words do hurt—mentally and physically—because targeted words supporting ethnic stigmas, even when folded into a joke, is such deeply entrenched racism that we would never know it was there without peeling back deep layers and shrouded history. This has been clearer than ever since the start of the pandemic when ‘eating bat’ jokes from friends made me cringe as they reminded me of the ‘eating dog’ jokes as a child. The stigma and xenophobia against Asian-Americans desolated and crippled Chinatowns and Asian-owned businesses from London to San Francisco before the virus even reached those shores.

When Donald Trump repeatedly and unapologetically described Covid-19 as “the China virus” in March 2020, the US’s Stop AAIP Hate coalition recorded more than 650 incidents of discrimination in just one week. Inflammatory rhetoric often starts as words, but can manifest as violence—and since the pandemic began, anti-Asian hate crimes have skyrocketed in western countries. In February 2021, CBS News reported that the New York Police Department (NYPD) had recorded an 867 percent increase in anti-Asian hate crimes, year on year. (NYPD has since formed an anti-Asian hate crime unit following the surge in incidents).

“I had a taxi driver immediately drive away in the pouring rain as soon as he saw I was Asian. Strangers would move to the opposite end of the subway car as I got on”

By now, Asian Americans are familiar with the story of 84-year-old Thai man Vicha Ratanapakdee, who was shoved to the ground in San Francisco in January and died two days later. Other horrific incidents include an 89-year-old grandmother who was set on fire last July, and a 61-year-old man slashed across the face this month. Meanwhile, in Paris, a Japanese man was recently attacked with acid.

These are just a handful of the attacks on Asian people that have come to light (many go unreported) since the pandemic started. This is the outrageous and infuriating reality that a lot of Asians living in western societies have had to minimise because of the notion that there are ‘more important things going on’. But Vincent Chin, Christian Hall, Ryo Oyamada and Ee Lee are among a long line of Asian people killed over the years. Say their names, too—and don’t say ‘we can’t pronounce their names’ as an excuse not to.

Asians targeted as the scapegoat

The irony is that China and other Asian countries such as Japan, South Korea and Singapore had significantly lower COVID-19 death rates than western countries. In the west, though, Asians today and historically have often been the easiest scapegoat.

In January 2020, I had been in Chengdu, China, for work when COVID-19 was first reported in Wuhan. On the 14-hour flight back to the US, everyone on the plane wore extra protection. I wore two face masks, gloves and glasses while sanitising my seat and anything else I touched.

“Instead of vowing to never let words hurt me, I’ve made a new promise to myself: to never let hate or rhetoric continue to silence or hurt my community”

But when we landed in Detroit for a connecting flight, the amount of open-mouthed staring from passersby made me realise that I had become a prime target. By the time I had boarded the flight from Detroit to New York, it was apparent that those around me viewed me as a direct security threat by simply wearing a face mask—I quickly decided the safest option for me was to blend in mask-less. Blending in is what we Asians excel at.

Later on, when I was viewing apartments in Manhattan in April 2020, I heard a couple mutter, “Get out, chink,” under their breath. I had a taxi driver immediately drive away in the pouring rain as soon as he saw I was Asian. Strangers would move to the opposite end of the subway car as I got on. As I biked around the city, I once almost crashed into a pedestrian as someone yelled at me, “Chinese bitch!” I kept repeating to myself, “Minimise, minimise, minimise,”—being called racial slurs was low on the list of priorities in the age of a pandemic. And they were just words, right?

Silence is no longer an option

But earlier this month, as reports of anti-Asian violence continued to increase, I decided it was time to share with my small yet mighty Instagram community about why we should care about the rise of anti-Asian hate crimes, alluding to our common enemy: white supremacy.

The unspoken trauma of Asian silence dates back to centuries of colonialism and imperialism, with the US’s 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act prohibiting the immigration of Chinese people. As author Cathy Park Hong recounted in The New York Times in April 2020: “In 1885, in what is now Tacoma, [Washington], white people terrorised the Chinese community by setting fire to their businesses. The xenophobia culminated in a riot in which a white mob drove 300 Chinese immigrants out of their homes, the mob chased the weeping immigrants out of town in a freezing rain.” Historically, other western countries once had Chinese exclusion laws too, including Canada’s 1923 Chinese Immigration Act; the White Australia Policy in 1901; and New Zealand’s 1881 Chinese Immigration Act.

When we say white supremacy, we’re talking about the systems that have allowed the enslavement of Black and Indigenous people while banning Chinese people from countries that weren’t even theirs in the first place. We’re talking about systems that continue to keep the oppressed divided so they may remain oppressed.

The real fight to be recognised and accepted

After speaking out on social media about anti-Asian racism, the hate comments started trickling in immediately, the most common being, “Go back to China and stay there.” When I sat in bed skimming through these messages, my vision started to blur and my heart raced until I slowly realised I was having a panic attack. Almost three decades worth of minimising racism erupting to the surface.

At that moment, it was apparent that I had silenced myself for too long—as it is in our Asian nature to stay quiet—I did not want this to be the case for the next generation. While we’ve read widely shared news of attacks on Asian elders, I was surprised that Asian-American youth have actually experienced the most hate crimes, according to Stop AAPI Hate data from February 2021. Words hurt, and that pain starts young.

So, for each of the hate comments I received targeting me and my community (around 500 out of more than 600 comments), I donated $2 per comment to Apex for Youth, a nonprofit organisation that provides mentoring and educational programmes to students of Asian and immigrant youth from low-income families in New York.

Instead of vowing to never let words hurt me, I’ve made a new promise to myself: to never let hate or rhetoric continue to silence or hurt my community—to do everything I can to transform this ignorance, xenophobia and hate into action and radical acceptance.

Here are some ways you can help the Asian community:

Report instances of anti-Asian assault and crimes at Stop AAPI Hate and Stand Against Hatred

Participate in a bystander intervention training at Hollaback!, a grassroots initiative to raise awareness about and combat street harassment, in partnership with Asian Americans Advancing Justice

Support and learn from #Hate is a Virus, a grassroots movement fighting racism and xenophobia that launched commUNITY Action Fund: raising $1 million to give back to programs related to AAPI mental health, better protections for elderly, representation and solidarity-building.

Learn from Act to Change, a nonprofit that published The Racism is a Virus Toolkit to support the community in combating racism

Sophia Li is a Chinese-American journalist and director based in Brooklyn, New York. Follow her @SophFei