“10s, 10s, 10s across the board!” The crowd erupts. At the end of the runway in a neon-lit room, a dancer clad in a sequinned jumpsuit strikes a pose, hair cascading glamorously and lips upturned in a fierce, sultry smirk. The panel of judges (who are dressed as fabulously as the competitors themselves) hold their hands out to give their ‘10s’—a stamp of approval—and the contestant moves on to the next round.

On the second floor of an inconspicuous, plain grey building on Cecil Street, Vogue in Progress (V.I.P.) is throwing one of the most highly anticipated events of Pink Fest 2023—the Pinki Kiki Ball 2.0. The energy in the room is infectious—the bass is booming and spirited chatter fills the air. Dancers, drag queens and audience members are seated along the runway and around the bar tables, all dressed to the nines with a drink in hand. They’re all here for one thing: a vogue extravaganza like you’ve never seen before.

Perhaps your idea of voguing has been loosely constructed by clips of RuPaul’s Drag Race or the old but gold Madonna song; or maybe this is the first time you’re hearing of it. The ‘vogue’ in question is not our magazine, but the dance style that bears its name. While it is pervasive in popular culture, the movement is mostly unknown to the Singaporean public. Here, Vogue Singapore takes a peek into the intricate world of Ballroom—all the beauty, glamour, and drama—and the burgeoning local scene.

A (very) brief history of Ballroom and the voguing subculture born from it

Drag balls first birthed the voguing subculture in Harlem, New York City. The dance style was initially characterised by sharp, angular moves—the ‘Old Way’—and evolved to the ‘New Way’ of voguing with moves we may recognise: the catwalk, duckwalk, spins, and dips, to name a few.

The LGBTQIA+ community was heavily ostracised and repressed—in conjunction with rampant racism—and the Ballroom Scene was one way Black and Latinx queer individuals rebelled against conventions and carved out a space for themselves in pageantry. The underground balls were a safe space for them to freely express themselves in a world bent on heteronormative outward expression. And above all, it was a way to find community—vogue houses (commonly known as Ballroom houses) were created by like-minded individuals, forming their chosen families that competed in balls and kept one another safe from violence and discrimination.

Over time, the Kiki subculture emerged from the Ballroom Scene. A less competitive, more lighthearted side of Ballroom culture—the term ‘kiki’ means to kick back and take things lightly—Kiki balls typically comprise performance and runway segments. With a myriad of categories like ‘Hands Performance’ which focuses on technical skills, or ‘Bizarre’ which gives contestants the freedom to experiment with fashion and design a positively outrageous and imaginative outfit, the runways saw dazzling handmade costumes and innumerous riveting performances.

And since its conception in New York, elements of Ballroom culture have seeped into public consciousness. Yet despite its far-reaching influence, most of us are incognisant of its roots and richness. Consider its inextricable ties to pop culture, for example. Much of the slang we use today can be accredited to the drag ball scene, made ubiquitous by the Internet—terms like ‘tea’, ‘shade’, ‘serving’, and the ever-affirming ‘yas’. And the music we love is inspired by the scene: Beyoncé’s record-smashing album Renaissance is an ode to Black Ballroom and club culture, with her world tour featuring unmissable performances by voguers—like Honey Balenciaga.

A closer look at the symbiotic relationship of voguing and fashion

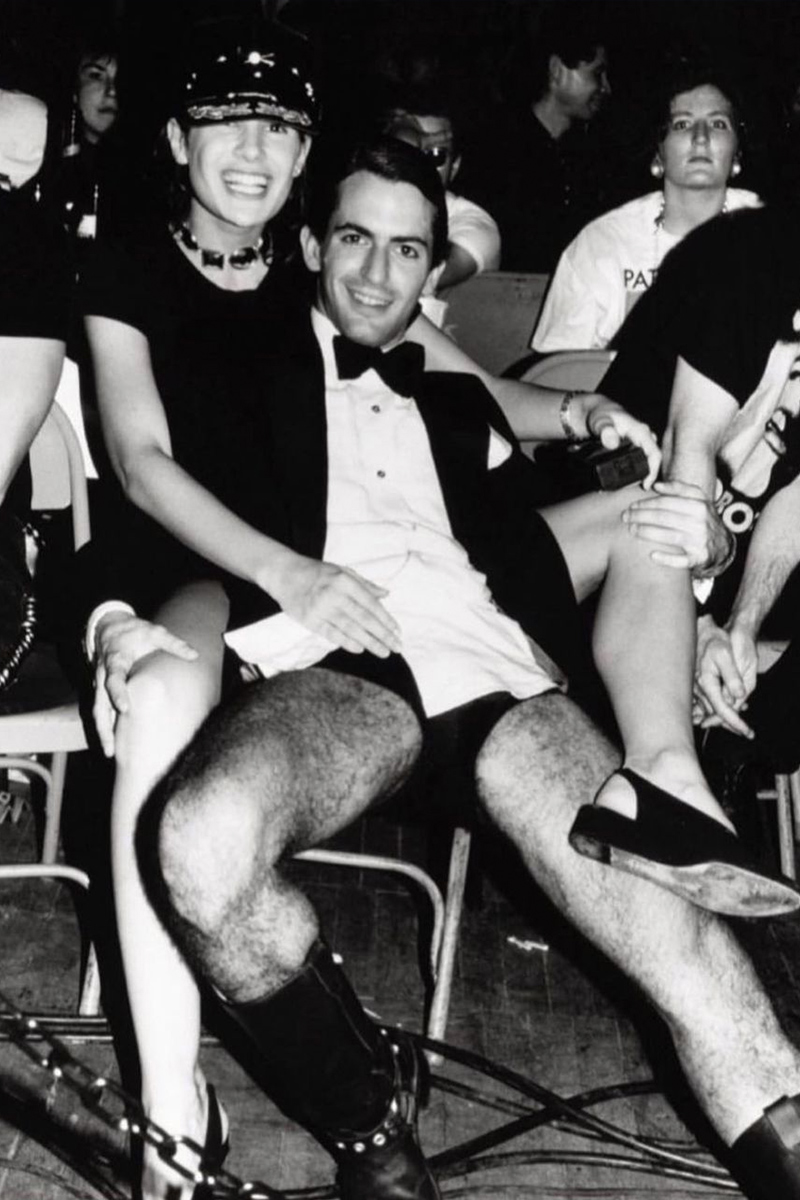

Voguing is intimately connected to luxury and fashion—many vogue houses have historically named themselves after iconic fashion designers or labels in an act of reclamation of the runway (which infamously excluded models of colour and queer models). The name also embodies the particular style and identity of the house. In 2020, voguing reality competition show Legendary premiered on HBO Max, with competing houses named after fashion giants Balmain, Gucci, St. Laurent, and Chanel—just to name a few. The designers themselves are no strangers to the scene either. In 1988, Marc Jacobs participated in a ball, which he described as “one of the most liberating, and, exhilarating experiences of [his] life”, and was made an honorary member of the legendary House of Xtravaganza. In 2021, the House of Marc Jacobs was launched with his blessing.

The runways of drag balls and Ballroom are a platform to showcase and celebrate queer pride, creativity, and artistry—and their influence on fashion is unmistakable. The looks donned by contestants are known to be extravagant, over-the-top, and all-around unapologetic. They embody campiness in the most delightful way. This fearless approach to fashion has indubitably inspired designers to utilise daring colours, dramatic silhouettes and eye-catching accessories. John Galliano’s early work is a noteworthy example. We can see the influences most clearly in Christian Dior’s 2003 spring collection—it was racy, campy, and glamorous. Christian Dior’s 2007 spring collection featured a vivacious colour palette, drag queen-esque poses and striking geometries, all interwoven with Japanese details.

The runway looks at vogue balls also challenge traditional gender norms, blurring the lines between societal expectations of masculine and feminine styles. This embracing of androgynous looks and posturings is a characteristic of vogue balls that paved the way for mainstream fashion to take a more inclusive and fluid approach to clothing.

Charles Jeffrey’s label Charles Jeffrey Loverboy embodies all these elements. Its bold, wonderfully eccentric designs are dreamt up in collaboration with “artists, performers, musicians, drag queens and poets”. Its resort 2024 collection, in keeping with the spirit of the brand, is an ode to the queer community—the multicoloured collection features gender-neutral pieces adorned with doodles and fun prints.

The voguers and drag queens who’ve inspired the industry have also been given the spotlight on the runway and in campaigns in the past few years. Drag queen Sasha Velour hosted an exhilarating drag show at New York Fashion Week for Opening Ceremony’s spring 2019 debut. At the Disney Villains x The Blonds spring 2019 show, voguing legend Leiomy Maldonado strutted, spun, and dipped. RuPaul’s Drag Race queens Gigi Goode and Symone starred in Moschino’s fall/winter 2021 campaign. And this year, the House of Marc Jacobs dancers featured in the label’s Pride campaign.

The blossoming Ballroom scene in Singapore—the glitz, glamour, and drama at the Pinki Kiki Ball 2.0

The subculture has since trickled down to our homeland, where the Ballroom scene is young and growing. In 2019, V.I.P. put on Singapore’s first vogue ball—The Crystal Ball—and the turnout was impressive. Stalled by the pandemic, they returned in 2022 with The Crystal Ball 2.0 and the Pinki Kiki Ball. This year, the second edition of the Pinki Kiki Ball was held on 17 June—and it was truly a spectacle to behold.

From evening till late, lively music pumped from the speakers, courtesy of DJs Bobby Obby Obby and C2ac, whose dramatic neon outfits illuminated from the booth.

Hosts Irzie KasiCunt and Jess 007’s opening remarks lay the groundwork for the event: “It is about chosen, found family; and in Singapore, we are celebrating local houses.” Sure enough, the show was certainly a “homage to those who have made statements in the scene”, with participants hailing not only from Singapore but from Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and other neighbouring countries. Rambunctious, colourful, and sometimes cheeky, the show was an exuberant celebration of Southeast Asian queer culture.

The distinctly Singaporean flavour of the show was exemplified most clearly in the ‘Butch Queen (BQ) Realness’ and Femme Queen (FQ) Realness’ runway categories. In these categories, queer participants aim to “pass” as heterosexual males or females respectively and are judged on how well they would blend in—a nod to the everyday efforts of repressed queer individuals to fit in. The ‘BQ Realness’ category saw a multitude of blue-collar and streetwear-inspired getups, one participant channelling a CBD businessman in a suit and workpack to the amusement of the audience. Meanwhile, the ‘FQ Realness’ participants were a picture of feminine elegance—one wore a lavish gown fitting for Miss Singapore, while another’s Y2K look was an ode to ‘Orchard Road Fashion’. All in all, a perfect encapsulation of Singaporean style and humour.

Across all the other categories, our local creatives undeniably showed out. From the Kiki House Of KasiCunt and The Kiki House Of Obsidian to all the ‘007’s (dancers without a house), contestants performed their hearts out in stunning “homemade couture”, as Jess 007 described it. Indeed, from the dripping gold outfits in the ‘European Runway’ category to the chrome galore in ‘American Runway’, it was quite the show—if the seemingly endless, roaring cheers were anything of an indicator. As host Jess 007 notes in awe during a particular round of futuristic silver outfits, “People here take kiki serious!”

Below, feast your eyes on some of the highlights from the Pinki Kiki Ball 2.0.

The world of Ballroom and voguing is intricate and beautiful, with a rich history to delve into—and it’s only one facet of queer culture that has made such an impact on the fashion industry as we know it. This Pride Month (and every month), uplift the community that continues to inspire designers, artists, and fashion enthusiasts to embrace creativity, individuality, and the power of fashion as a form of self-empowerment.