In the 1960s, The Beatles was born. And through the ecstatic years that followed the international pop sensation, something else entirely brewed in plain sight: Beatlemania. The term used to describe the frenetic female-led fan culture that followed the quartet—namely John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, or Ringo Starr (who replaced Pete Best as the band’s drummer)—everywhere they went. As they belted their hit singles that sang of giddy romance, from ‘She Loves You’ to ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’. Tour destinations in turn became opportune moments when fans could swarm the barricade hoping for a shoutout or the smallest interaction between them and their “favourite Beatle”. And merchandise, from posters and badges to lunch boxes, wallpapers and magazines, were absolute profit making machines once you slapped them with The Beatles brand.

Sound familiar yet?

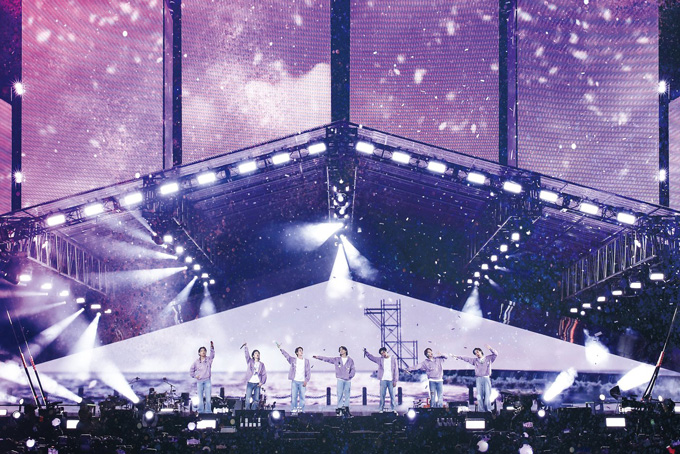

A few years ago, it might have been One Direction, and a few decades before that, it would have been the Backstreet Boys. In today’s context, perhaps it would be BTS. Or rather, what the septet stands for: the behemoth that is K-pop. After all, we’re merely mapping out who comes close to igniting the same visceral reaction in each generation’s youth. But lean a little closer into the most hyperbolised fan culture of today, and one might discover that there is nothing quite like the relationship a K-pop fan shares with their favourite idol. And yes, I use the word—and very carefully here—’relationship’.

Critics would be quick to call this ‘delusional’, ‘problematic’ or ‘toxic’. After all, I am potentially implying a two-way affair: between an idol, and their fans. But it’s one that seems difficult to believe, especially when the truth (and common critique) of the matter is that most of these idols could never possibly get to know each and every single one of their fans. And herein lies the first signs of the parasocial relationship—a contested topic through the decades, for a phenomenon that has only been blowing into epic proportions with leaps in new tech and social media.

The parasocial relationship, typically defined as a one-sided relationship where one party expends an overt amount of time, emotional energy and even money on another figure they find fascinating, but who doesn’t know they exist. These figures are often celebrities, social media influencers, game streamers or even animated characters. In this sense, anyone who sees themselves as a fan of a certain personality can then be considered to be in a parasocial relationship—but the question stands: is it detrimental and toxic or is it actually reasonable and healthy?

There are varying degrees to which someone considers themselves a ‘fan’. And yet, if you’re living in today’s age, you’re probably learned of how K-pop fan culture is a force to be reckoned with, all on its own. The sheer intensity of K-pop fans is one that confounds dozens—from the presence of bewildering fandom names to fabulously-shaped lightsticks and the many, many lengths to which a K-pop fan might go to just to see their favourite idols in real life. The famous marketplace of collectible ‘photocards’ are an entire battlefield in its own right, with these once mere album-accompaniments transforming into the very reason fans continue to buy physical albums despite the digital age we live in.

Sure, some of it veers into very strange territory. But it’s a hobby—albeit a very complex one—all the same. And with every hobby out there, interest groups are formed, where people find like-minded others to bond with. In the same way, fandoms of idol groups exist and cooperate as a whole community. Each one called by a different name seemingly linked to the idols themselves; BTS (Bulletproof Boys) has the ‘Army’, Mamamoo playfully calls their fans ‘MooMoos’ and ‘Blinks’ are derived from Blackpink’s name.

It’s a sense of belonging like no other, and it’s only bettered by the social media platforms they have wielded with unrivalled finesse, most prominently Twitter. The Twitter verse offered a space like no other: for both idol groups and their legions of fans. Whilst the former could directly engage and form more humanistic connections with their fans, the latter could feel like a part of a bigger something—as they joined in on achieving ‘comeback goals’, took part in fandom-led donation campaigns or simply connected with their fellow fans, making new friends in the process. For some, the fan-friends they made online were the people they could find solace in—a little respite bubble away from the issues they face in their personal lives.

Soon enough, this level of interaction between fan and idol became an essential reason as to why an increasing number of fans became drawn to the K-pop sphere. It was undeniably catapulted by the introduction of VLIVE (now Weverse), a live video streaming service with in-app translations that allowed K-pop artists yet another way to directly interact with their fans, with fans utilising the chat function to ask questions and comment on what their favourite artists were doing or saying in real time. Adding to that was SM Entertainment’s DearU Bubble app: a service that allowed artist-specific content to be personally sent to paid users—like a chat message would—who could then in turn reply to them directly. And of course, with the pandemic, came the meteoric rise in online fan meetings, aka real-time video calls that would allow various fans to speak to their idols and biases directly.

View this post on Instagram

Granted, these periodic updates or random check-ins from one’s favourite artists might not seem like much to the outside eye. But perhaps when it comes from someone you so deeply admire, it makes more of an impact than one would think. At times, they’re reminders to take a mental health break. At others, they’re healing messages or simple words of affirmation for the person that you are, whoever you are. And every so often, they’re candid confessions of their own personal hardships—making them that much more relatable.

Of course, whilst these interactions might encourage some to veer into the dangerous tendencies associated with sasaengs, a pathological fan who obsessively stalks or believes they have the right to know everything about the artists’ lives, it’s also become a part of common idol-fan speak nowadays to remind one another about creating a healthy environment for both parties. BTS’s ‘Pied Piper’ was a witty reminder that no fan should neglect their personal responsibilities just because of them. Super Junior’s Kyuhyun was previously known to have vocalised his disappointment in fans who would stalk and mob them at airports. Seventeen’s The8 often comments on the nature of parasocial relationships during his livestreams, reminding fans to be careful of their fantasies.

With idols growing increasingly comfortable with drawing boundaries and fan communities evolving to be healthier spaces that keep each other in check, what remains is a unique place to be. A place that even idols themselves seek solace in; many of them having openly admitted that it’s a special relationship all on its own. A number of idol groups have dedicated entire songs to their fandoms alone: think ITZY’s ‘Trust Me (Midzy)’ or GOT7’s ‘Thank You’. When asked if he understood how his fans feel in a Weverse interview, Soobin of Tomorrow x Together (TXT) described it with tenderness: “I think there’s a certain kind of love that can only exist between a singer and their fans—one that doesn’t happen between friends or people dating. They exist for each other and want each other to be happy and hope for better things for the other than for themselves. It seems like it really only exists between fans and singers.” Now, more than ever, it’s a two-way street, even in its own lopsided little way.

What’s not to love? It’s a running joke amongst most self-aware fans that the parasocial relationship they share with their idols is one that’s stable, filled with love and unlike real-life relationships, they’ll never disappoint you because you’re not actually expecting anything from them. And when you combine the foolproof music releases, weekly variety shows and a seemingly endless stream of behind-the-scenes content almost every K-pop group or idol seems to have, the result is an entire universe you would always appreciate being a part of. A little world—promising an indescribable happiness of its own.

So pray tell: is it actually good for us? It’s a fine line for sure, but tread it well, and perhaps one day, you’ll be telling the wildest tales of the years you held a lightstick in hand, waiting on the ones who shined like a beacon in your lives.