It’s not hard to understand why artists are concerned about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in art. At Colorado State Fair’s annual art competition in 2022, a prize was awarded to an artwork that was, unbeknown to the judges, generated by AI. This year, a class action lawsuit has been filed against a trio of AI text-to-image generators, alleging that the data sets used to train the platforms’ algorithms made use of billions of copyrighted images without compensation or consent from the artists.

For artists, seeing a computer imitate and manipulate work intrinsically tied to their identity can be devastating. Some even wonder if jobs that would have gone to them might start going to machines instead. To Singaporean artist Jo Ho, however, AI is just another tool.

Shiny new tools

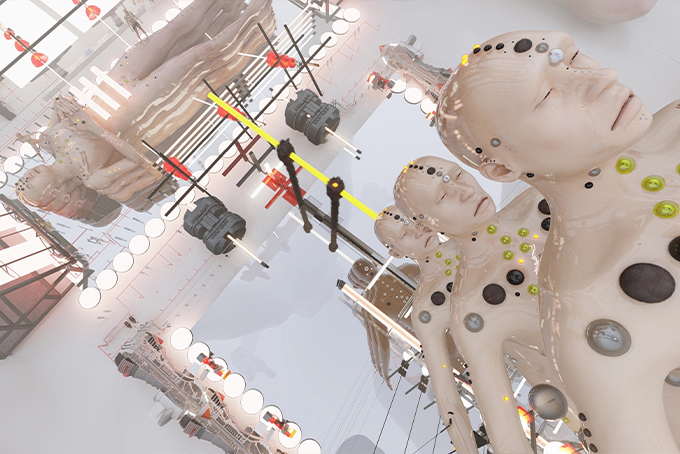

In her artistic practice, Ho experiments with emerging digital technologies—including the use of AI—to create works that examine the future of digital interactions between us and our environment. She points out that the use of AI in art is more established than most might imagine. “AI has already been prevalent in the tools artists and designers use in our software, such as Content-Aware Fill in Adobe Photoshop. In its current state, AI is just another tool that belongs to the wider sphere of generative art. Although generative art has been around for more than a century (think of Marcel Duchamp’s ‘3 Standard Stoppages’ in 1914), the idea of generative approaches in art using computer algorithms is relatively new.”

Rather than shunning the technology, she believes that it is important to continually question the way these tools get developed, the types of people developing them and the specific ways in which they are being used.

Kuala Lumpur-based artist Chong Yan Chuah, who uses AI to supplement and inspire his work, views the adoption of new technology with a certain sense of inevitability. “It’s the natural progression of things. As we evolve, we take up new tools and discard old ones. That’s how we have advanced to where we are today, both in life and in art.”

“What makes art original is the lens that artists view the world through.”

When it comes to the controversial issue of text-to-image AI platforms being trained on the works of real artists, Ho understands the increasing concern. “I certainly would not like it if someone’s data set was heavily influenced by my work without asking for my permission or offering compensation, especially if the others can then profit from the application,” she points out. Yet, she also feels that much of the present criticism is misplaced. “A lot of hate has been directed to the AI artists that have emerged from the publicly accessible text-to-image generators, but I would direct the criticism to the makers and profiteers of the tool.”

Using other artists’ works as reference or inspiration, Chuah points out, is something that artists have done long before AI came into the picture. “As artists, we are all inspired by a range of different things that we curate—much like an AI learns from its data set. But what makes our art original is the lens that we view the world through. When you look at an artist’s works, you are also witnessing their perception of art and the world. In that sense, an AI can’t offer anything original, and an artist’s works will always hold more value.”

It makes sense, then, that some artists might see the tool as an asset rather than a threat. Ho says: “As a designer, the most efficient way for me to utilise AI is to make my workflow faster by letting it complete repetitive and mundane tasks for me.”

Drawing the line

In her usage of AI, however, Ho strives to be careful with her process and sources. The line between what might be considered ethical and not is extremely fine when it comes to the use of AI in art.

“It’s not easy to define where the boundary lies,” she acknowledges, “I try to be as ethical in data collection as I can, within provided means. Since I do not code my own AI algorithms, I instead take time to investigate the programs that I use. How much control do I have over the data set? If I collect my own data set, where am I getting these images? Are they for the general public, or are the images protected with copyrights? Could I ask for permission to use them?”

Beyond that, she questions her choice to utilise the technology. “After initial experimentations with the technology, I ask myself why I’m still using it. Does creating with AI still serve a purpose? If not, are there other tools that I could use instead?”

Another factor to consider is the extent to which a completed piece of AI art is the original expression of the artist. Chuah explains: “Even if I use AI in my art, I use it as a tool to guide, complement or inspire. The final click of the mouse, the finishing touch of my hand—that’s all mine.”

Embracing the unknown

At the end of the day, the technology has already been established. “The focus now should be on how to improve its usage for artists,” Chuah says. A way to identify and authenticate the human artist when an AI is trained to create art like them, he points out, could be a useful tool.

The hope is for regulations surrounding the technology to catch up with its rapid progress. Ho explains: “Most of these programs have no precedents and were built without any laws and legislation in place. As with any new technology, the laws surrounding AI-generated art and intellectual property are only just starting to be built, and will continue to be refined.”

It’s reasonable for artists to be wary of the new technology, but Ho hopes that it opens up conversations on the way we define art. “The conversation surrounding AI is a catalyst for the world to understand that there is a whole community of artists who create art using generative, autonomous systems and computer algorithms. I believe that some level of scepticism is healthy and creates important dialogue. For most, the doors to generative art have just begun to open.”

For more stories like this, subscribe to the print edition of Vogue Singapore.