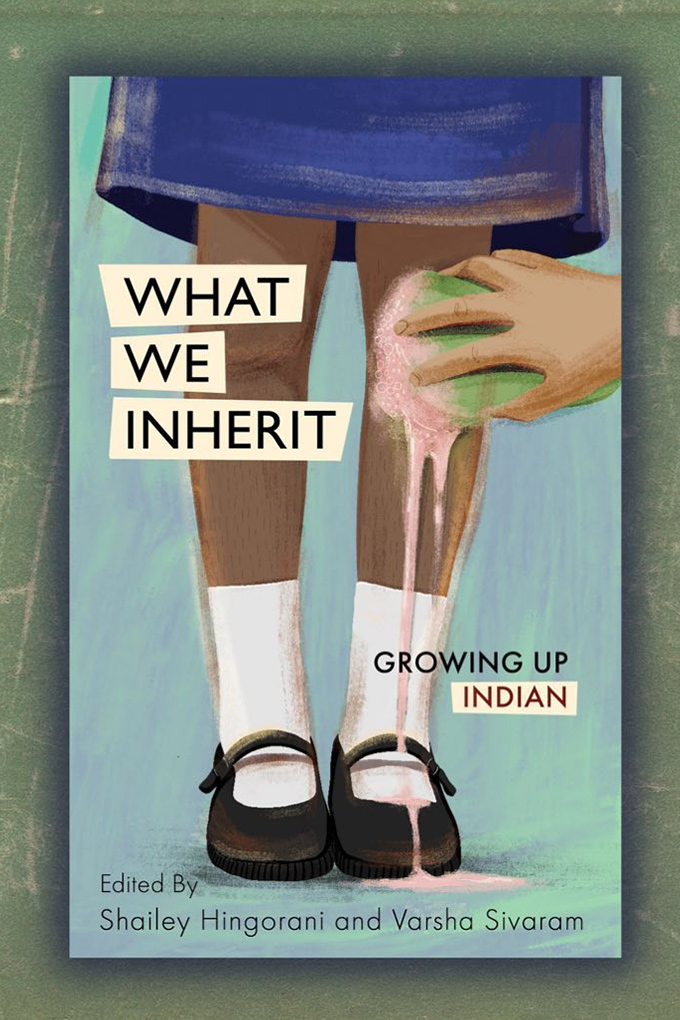

As an Indian woman, one of the things I have persistently struggled to write about is the intersection of those two facets of my identity. Growing up Indian in Singapore has borne some of the richest joys and greatest traumas of my life, and similarly polarising has been the experience of being a woman. To capture in words all the nuanced ways gender and heritage come together to shape our lives is no small task. Endeavouring to do just that, however, is a beautifully-composed new anthology, What We Inherit: Growing Up Indian.

Written by Indian women (and a few men) in Singapore and published by women’s rights organisation Aware, the book holds within it a staggering 38 personal essays, all seeking to archive the experience of living in brown skin on our island. Contributors to the title include seminal activists like Constance Singam and celebrated writers like Balli Kaur Jaswal and Pooja Nansi, amongst a truly wide and varied range of voices each with a unique story to tell.

The collection has been edited by Shailey Hingorani and Varsha Sivaram of Aware. Hingorani, who has been a women’s rights activist in South and Southeast Asia for over 13 years, is presently Aware’s Head of Research and Advocacy, while Sivaram is a Senior Projects Executive at the organisation. Together, they embarked on the process of putting together the collection, beginning with an open call for Indian writers in Singapore that saw overwhelming response.

“Narrowing down the essays and poems to include in the book was immensely challenging. Every submission we received had something valuable to offer, especially in how honest and vulnerable they were,” says Hingorani. “Every story taught us something new—about ourselves, and about what it means to lay bare your stories of pain, grief and joy.”

“We were on the lookout for visceral essays that would resonate with Indian and non-Indian readers alike, as well as readers of all genders”

The result of their painstaking—but worthwhile—labour speaks for itself. Poignant, diverse and delicately nuanced, the book is a rich cultural treasure trove, with each deeply personal essay offering a valuable glimpse into the lives of Indian folk in Singapore. Parsing through the ways we face adversity and find community, these stories will make you laugh, cry and feel seen like never before. Here, Hingorani offers deeper insight into what it took to assemble this historic project, and what she hopes it will achieve.

What did the process of putting What We Inherit together look like?

We started with an open call, asking Indian writers to send their essays and poems about growing up Indian in Singapore to us. While we prioritised women’s voices, we made it clear that people of all genders could submit their work. We noticed that many writers asked us whether their stories—and even their identities—were “Indian enough” to qualify. The idea that one needs to be “Indian enough” to have their stories included in the canon of Indian women’s literature was something we avidly sought to dispel, both in the open call and as we began crafting the anthology itself.

This sentiment, combined with the fact that many writers were new to the form of the personal essay, led us to conduct a writing workshop with the assistance of Balli Kaur Jaswal. During the workshop, writers shared more about their insecurities, their experiences with discrimination and their richly diverse ideas for personal essays. For us, this experience demonstrated how impactful solidarity between Indian women writers can be.

The book does a fantastic job of capturing the nuances that colour our experiences growing up Indian in Singapore. What was your editing process in ensuring that would happen?

With these essays and poems, and with how the anthology is structured, we sought to ensure that we weren’t boxing any contribution into a narrow category. We didn’t want to definitively state that a certain essay was “about race”, or “about gender”, and so on. Indian women’s experiences have so much dimension to them—we grapple with colonial pasts, gendered expectations, complex relationships with the idea of family, and so much more.

To that end, we tried our best to give essays and poems the room to breathe, and to cover as many topics as they needed to. We also organised the anthology into wide-ranging sections: “What We Inherit”, “What We Endure”, “How We Speak”, “How We Identify” and “How We Find Joy”. And even within each section, the writers’ own identities and personal experiences have significant divergences between them—they come from different backgrounds, speak different languages and have different perspectives.

The quality of writing is consistently excellent throughout the anthology. What guided your selection of contributors?

Selecting contributors was a tough task, given how much talent we were seeing in our submissions. While some of these writers are established names in fiction and non-fiction, a number of them were approaching writing about their personal lives—and even writing at all—for the first time.

“Indian women who chart their own path in life often come up against this concept of ‘troublesome’ womanliness”

Emotion was a significant factor that guided our selection. We were on the lookout for visceral essays that would resonate with Indian and non-Indian readers alike, as well as readers of all genders. We were also looking for essays that documented Indian experiences in Singapore that many might not be familiar with—stories that toyed with the boundaries of CMIO (Chinese, Malay, Indian or Other) and voiced the nonconforming or “taboo” parts of being an Indian woman out loud.

Which essays in the book personally resonated with you the most?

Picking just one or two of the 38 personal essays and poems in What We Inherit is definitely a difficult task. To me, one essay that stood out was “School Colours” by Sujatha Raman. Raman reflects on a Tamil teacher she had in her childhood, and how his experiences with racism and discrimination impacted her. It resonated with me particularly because it shows readers the cost of self-advocacy—in the essay, individuals who speak out about facing racism are met with dire consequences, simply for voicing their beliefs.

Another essay that stands out is “A ‘Troublesome’ Womanliness” by Matilda Gabrielpillai. The essay chronicles her childhood and coming of age as she grapples with conservative traditional expectations. Indian women who chart their own path in life often come up against this concept of “troublesome” womanliness, and the author’s musings on the subject really resonated with me.

What do you hope for Indian women to receive and experience through this book?

We hope that Indian women are able to find solidarity through What We Inherit, and are able to see that their personal experiences can be a profound avenue for advocacy and change.

To write these essays and poems individually is no mean feat, but the act of placing them together, side by side, represents just how much nuance and breadth there is to Indian women’s experiences in Singapore. This is something that Indian women already know, of course, but we hope that seeing it compiled and published in a book like this is affirming. We hope it confirms that our stories are powerful in and of themselves, and that they don’t have to be gate-kept by other parties to be considered legitimate.

“Listening and learning are acts of humility—they require us to turn inwards, face our fears, and do the work”

How do you suggest non-Indian readers and readers of other genders approach this book?

I hope that people reading the book will recognise the need to invest in each other as complex individuals. As readers, we need to confront the voices in our heads that tell us that some stories are unimportant. To that end, approaching this book with an open mind is vital. As readers who might be new to these topics read this anthology, asking questions about subjects like race and gender should also be done with the intention to understand, rather than to retort or argue.

Listening and learning are acts of humility—they require us to turn inwards, face our fears, and do the work. We hope that non-Indian readers and readers of other genders are open and willing to do this.

Looking forward, what sort of change do you hope this book will inspire?

Through this book, I hope that readers start noticing the inequalities around them, if they have not done so already. I hope they recognise that we aren’t taught to be explicitly anti-racist in this society, nor are we are trained to see how seemingly un-racist policies can produce racist outcomes.

These perspectives take time and effort, including the ability to see past our own prejudices. I hope the book will be a start of a new kind of consciousness, geared towards noticing and resisting inequality.

‘What We Inherit: Growing Up Indian’ is available at ethosbooks.com.sg