Béton brut (a French term for ‘raw concrete’) refers to the use of concrete in a way that leaves it unfinished. It was made popular by modernist architects such as Auguste Perret and Le Corbusier. The latter started using the term when referring to the construction of Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, France. It was a concrete apartment block built in 1952 that architectural enthusiasts and students make pilgrimages to today. From the modernist movement came brutalism. The architectural style that emerged during the same era in the UK employed raw materials and celebrated the form of structures with overapplied decoration. Exposed concrete as well as unpainted brick and steel were common materials, as were geometric shapes and subdued colour palettes.

The style inspired the design of a penthouse in Singapore by Dennis Cheok, who runs cross-disciplinary design studio UPSTRS_. In fact, he christened the apartment Béton Brut. Raw concrete surfaces, monochromatic tones and a subdued lighting scheme define the voluminous space, where owner Neil Yang lives and works.

Like the enigmatic space, Yang is discreet, preferring to remain unidentified (the name is an alias). But he willingly offers his take on the style that inspired his home design. “I’m a huge fan of science fiction media, and brutalist architecture is featured in a lot of science fiction film and television, which is probably what drew me to it initially. Brutalism is often criticised and perceived as oppressive, but I think that’s somewhat reductive of what this style can convey. Arising in post-World War Two Europe as it attempted to rebuild from the war, its austere appearance and use of raw concrete was a rejection of the ideologies of before and an attempt to rebuild society in a new image,” Yang expounds.

“We fell in love with the raw sculptural honesty of brutalism, which led us to the fundamental principles of béton brut”

The unembellished textures and neutral tones of raw concrete are a blank canvas for Yang to fill with his own identity and life. Many tomes fill the niches of the library that rises up the double-storey open living and dining area. Graphical artwork reflecting his interests also forms a visual narrative through the home.

Yang was drawn to the condominium development’s idyllic surroundings as well as the high ceilings of the penthouse that enabled a sense of openness and spaciousness despite its modest footprint. “A brutalist-inspired space can appear overbearing. But when paired with the large open space from the high ceiling, I think it can also convey both calm and awe,” Yang shares.

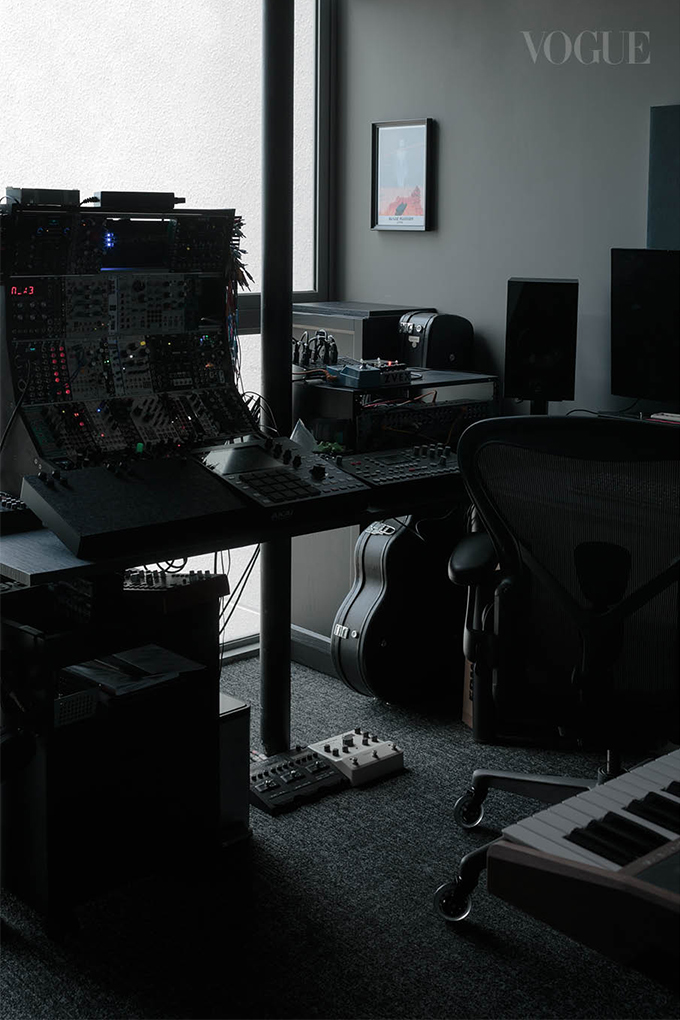

The self-employed software developer works from home, thus he wanted the space to be open and yet have some sense of compartmentalisation so he could switch between activities easily. Yang is also a music buff and makes electronic music as a hobby. Electronic equipment, several electric guitars and a keyboard in his music studio give clues to this obsession.

“I’m heavily inspired by electronic music, especially experimental artists like Autechre and Alva Noto. I’m quite fascinated with the unique sounds that electronic music instruments can create, and I think the sonic possibilities in electronic music are far greater than in other genres. I suppose you could say my fascination with unique sounds and textures in music mirrors my fascination with the textures and tones in brutalism,” Yang enthuses.

“How it feels to the touch or how it diffuses the light, or the way silhouettes of walls and furniture crossing and intersecting create intriguing geometrical patterns”

He describes his childhood self as a “fairly nerdy kid who spent most of the time on the computer, left mostly to his own devices”. As he started getting into making electronic music, he amassed so much gear that his childhood bedroom became claustrophobic. This was when he decided to move.

He found affinity in the work of Cheok, whose passion and background in theatre governs his narrative approach, and whose architectural training introduces temperance and formal dexterity. Cheok, who has a penchant for irreverence, the avant-garde and the sensual aspects of life and living, was equally riveted by Yang’s brief.

“We have received countless email enquiries over the course of 12 years running the firm, but this was a brief that I will never forget. Firstly, it was impressively detailed for a preliminary enquiry comprising full timelines, mood boards, scope of work and even two accurately planned layout options with specific planning requirements down to the millimetre, particularly for his music studio equipment,” Cheok recalls.

He adds, half in jest: “I can still vividly recall the layout diagram filled with so much information and details that the mark-ups were rows of tiny little text next to rows of thin, skewed lines filling up the page, forming a mind map of sorts. I thought he must either be a genius or a serial killer.” One particular picture in the mood boards that had him sold depicted a moody, cavernous concrete volume, with slivers of light streaming through an aperture overhead and beautiful shadow play over its textural surfaces. “As a nod to the project genesis, we wanted to evoke the misty shadows of that world in the photographic documentation of his home,” he says. The first step was to open up the original space, which came with two en-suites, a compact kitchen and living room. “Being on the top floor, what was striking was the four-metre-high ceiling and a master bedroom on a loft,” adds Cheok.

A bathroom and bedroom at the front of the apartment were removed, enabling a connected living, kitchen, dining and study. The latter Cheok delineated as a long table with tall, one-way mirrored panels that allow vistas from the study but obscure clear views from the surroundings. It overlooks the other spaces like a‘mothership’ in a villain’s lair.

As one enters through the main door, the dining table and kitchen island counter—orthogonal blocks conceived as objects in the space and positioned adjacent to each other—forces careful navigation into the rest of the space. The elevated master bedroom at the end of the unit floats above the music room, reached via a nascent of steps with a single thin metal rail.

“The formal design process was a deep dive into Neil’s mind,” says Cheok, sharing that the duration of the project took place in March 2022 when the borders had just reopened from pandemic lockdowns. “Neil took a trip to London and we saw the world through his lens. He shared with us a series of architectural details from brutalist architecture through images he took. We diligently captured and documented forms, details and textures that caught his eye and formed the spatial, material and textural vocabulary for this extraordinary design exercise. We fell in love with the raw sculptural honesty of brutalism, which led us to the fundamental principles of béton brut.”

He imagined the raw, bare space as a private world, with extruded volumes and carved-out spaces akin to a miniature city. “Textural, concrete plaster treatments and the marks of its making became the unifying language. A rhythmic concrete shell mirroring the concrete facade of buildings formed the library,” he highlights. Plentiful storage is hidden in cabinets that rise to the ceiling, clad in gunmetal steel to reflect the daylight from the full-height windows spanning the common areas. The only exception is the bedroom, which Cheok cloaked in timber for a warm contrast. From here, glass apertures connect the sleeping zone to the other parts of the home.

The play of light and shadow, of dark and light, mass and skin add interest to the monochromatic interior. “We spoke in terms of light and shadow, and thought in terms of day and night transitions in the space where natural light falls and reflects, where shadows and textures are created, where screens are shut and curtains drawn, and where Neil finds his sanctuary and safe place,” Cheok elaborates.

The bathroom is the darkest space in the home, clad in dark textured granite and accented with a plinth-like vanity basin.“Neil wanted it to be almost monastic in quality,” says Cheok. Deep discussions between client and designer reflect shared poetic sensibilities and understanding. “We spoke about the needful insertion of life through a singular blooming plant in his balcony, which he aborted; and at the other extreme scale, sculptural mosscapes that he now has a collection of,” Cheok shares.

Among the many unique aspects of this project is a ceiling that is almost void of lights, save for a single spotlight casting a dramatic glow over the kitchen island. It is apparent that this part of the house is not just for show. A rather substantial collection of condiments arranged neatly on the counter is evidence of someone gives thought to the cooking process, though Yang shares that it is mostly for practical reasons as he works from home.

“Unfortunately, this also means I try not to spend too much time cooking different kinds of things, but instead, stick to the same kinds of meals for weeks until I get bored and figure out something else to cook for the next few weeks,” he adds.

Within the seemingly abstract shell, the visceral, human aspects of everyday life play out. The home is a receptacle of smells, textures, sounds and scenes of a life lived intently and intensely, anchored and yet fluid. “At the end of the day, the comfort that seems to work so well experientially helped him to create a fort-like world where he feels safe to live, rest, wander and create,” expresses Cheok aptly.

This observation rounds up the discourse with Yang on brutalism perfectly. “Despite its contemporary reputation, I think brutalism is quite a humble architectural style. After all, its focus is on the raw quality of simple materials, an inherent fascination with the plain textures of concrete or wood. How it feels to the touch or how it diffuses the light, or the way silhouettes of walls and furniture crossing and intersecting create intriguing geometrical patterns,” he says. “In many ways, these are the same sort of qualities that we as humans find alluring and calming in nature except in brutalism, it’s the qualities of human-made materials. Yes, brutalism is a blank canvas for our human lifestyles, but canvases have textures too and those textures shape the paint that is laid upon them.”

Order your copy of the September issue of Vogue Singapore online or pick it up on newsstands now.